We spend a lot of time here at FanGraphs writing about breakouts. A player who’s suddenly figured it out represents both an exciting piece of news and a chance to dive into the nuances of pitching or hitting. Reading and writing about that subject so often makes you pick up on certain patterns. Today, our subject is Brett Baty, who hasn’t played enough to qualify and who hasn’t broken out in a big way, but who is fascinating because his breakout doesn’t quite match the patterns we’re used to seeing.

Baty came into the season with a wRC+ of 71 over three seasons and 602 total plate appearances. He’s 25, and he’s had an up-and-down career, mashing his way up the Mets system and then struggling once he gets the promotion to Flushing. He’s got an .889 OPS in the minors and .654 in the majors. If you were to ask a Mets fan what Baty needed to do in order to succeed this season, they probably would have said he needed to put the ball in the air more and he needed to stop striking out so much.

Over 326 PAs this season, Baty has doubled his career home run total of 15 and he’s running a 107 wRC+. These are huge improvements. But he’s still striking out too much and he’s running a career-low launch angle. That’s not the only mystery. Baty is hitting the ball harder, going from an average exit velocity of 88.8 mph from 2022 to 2024 to 90.8 mph. Adding two ticks of EV is huge. His hard-hit rate has also jumped from 40% to nearly 47%. But once again, his increased contact quality doesn’t fit the patterns we’re used to seeing.

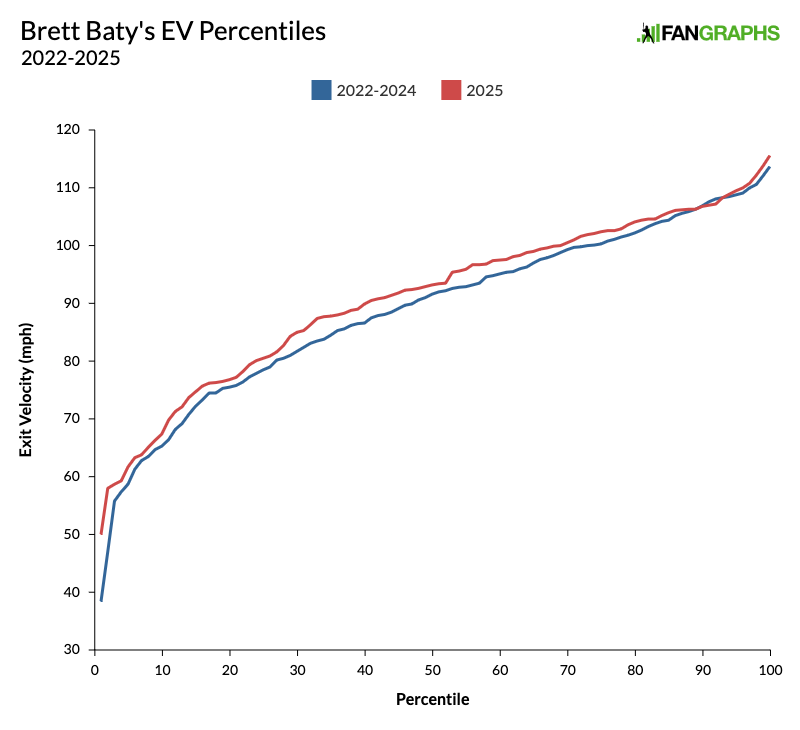

When we see a player’s average EV go up, it usually goes up for one of two reasons. First, they could have developed more top-end power. When that’s the case, we see their 90th percentile EV tick up. Baty’s EV90 this season is 106.9 mph. That’s exactly the same as the career mark he had before the season. Although he has hit the hardest ball of his career this season, I don’t think we can say he has found a new gear. The second option is that the player could cut out the mis-hits. Baty hasn’t really done that either. According to Sports Info Solutions, he’s running a 19.5% soft-hit rate, compared to 15.2% in the three previous years. Statcast tells us that 24% of Baty’s batted balls this season have been below 80 mph, compared to 26.7% in previous seasons. Those are the two usual ways of improving your EV – raising the ceiling or spending less time on the floor – and Baty hasn’t done either. That just leaves the contact in the middle.

The blue line in this graph falls off a cliff. Baty hasn’t unlocked a new gear of power, and his mis-hit rate is roughly the same. It’s just that he’s turned a lot of that medium contact into hard contact. I broke down his exit velocity percentiles to show you what I mean.

These two lines stay very close to each other for the entirety of the graph. The biggest differences come right around the 35th and 55th percentiles. That’s a big deal because Baty hits the all-important hard-hit threshold of 95 mph right around the 50th percentile. So although he’s not blasting more balls at 110 mph, he’s still hitting more balls that can do real damage. Baty has cranked up his median contact level by increasing his average bat speed and his squared-up rate. That’s a great two-fer, but it’s not always easy to do those things as the same time. Swinging harder and squaring the ball up tend to work in opposition, but the context matters here. Baty’s bat speed is up not because he can swing harder – of the 10 hardest tracked swings of his career, six came this season and four came in previous seasons – but because he’s doing it more often. He’s dropped his chase rate and is swinging at better pitches.

This would also be a good time to mention that Baty’s swing is completely different. He’s has narrowed his stance by more than 12 inches, closed it by four degrees, started turning his front foot inward like Juan Soto, and added a leg kick. That’s a lot of changes – which tends to happen when you’re struggling for multiple years to catch on in the majors – and we’re not done. Baty’s swing is also much, much flatter this season, and to some extent, it’s because he’s completely changed his approach. He’s much more focused on higher pitches on the inner half (which naturally result in flatter swings because he’s not going down to get the ball).

This is a huge change, and there’s more. Baty is catching the ball much, much deeper and hitting the ball the other way much more often. Once again, his pitch selection is informing this to some degree – high, inside pitches are especially hard to get around on, so their intercept point can be deeper – but Baty’s still an outlier here. If you split the strike zone into thirds and look at every left-handed hitter with at least 25 balls on high pitches that are either inside or over the middle, Baty’s 18.5% pull rate ranks 91st out of 95 batters.

The strange thing is that Baty’s intercept point is especially deep when he’s taking his best swings. If you look at hard-hit balls, his average intercept point has dropped from 28.9 inches in front of him in 2024 down to 25.7 inches in 2025. If you look at pitches over the heart of the plate, it’s fallen from 28.6 inches all the way to 23.3. In all, his average intercept point is 25.6 inches, deeper than 89% of all batters (minimum 500 pitches seen). He’s dropped from the 40th percentile to the 11th. By any standard, he’s catching the ball extremely deep. That’s not usually a recipe for increased power. When we think of hitters who catch the ball deep, we think about contact hitters who stay back and spray the ball the other way. But despite his many struggles to take advantage of it, Baty possesses the kind of bat speed that plays to all fields. Like anybody, he hits the ball harder to the pull side, but he hits the ball hard enough that he doesn’t have to pull it to do damage. Here he is smashing an inside pitch into the left field gap for a double.

That is so, so many changes. Baty’s stance is different. His timing mechanisms are different. He’s swinging harder at different pitches, meeting the ball deeper, and pulling it less. And he’s still not elevating it all much more than he did before. He’s made so many adjustments over the past few years that it’s hard to know where one starts and another ends, let alone which ones could be responsible for his improved performance. Even now, it’s easy to look at Baty and expect bigger things. He’s way too patient and way too powerful to run a 107 wRC+. But he’s also had just 326 PAs this season. It’s not exactly a big enough sample to say that this is who he is now. Maybe he’ll get to yet another level or maybe he’ll regress some. Still, running an above-average batting line is a big step forward.

Content Source: blogs.fangraphs.com