Some days, we analyze all of baseball here at FanGraphs, and maybe come up with some tools that will help predict all of future baseball. Injury-aware depth charts, payroll matrices, top prospect lists: You get the idea. Today, however, is not one of those days, at least not for me. That’s because after watching some videos of Tyler Soderstrom being very strong, I tried to figure out whether his early-season success will continue.

Being very strong is a valuable skill, at least when it comes to hitting a baseball. People don’t ooh and aah over Aaron Judge because his name makes for a fun fan section; they do it because he hits the ball so far. There are countless different ways to be good at hitting, but let’s be honest with each other: Being really strong is one of the best ways. Chicks don’t dig the well-placed opposite field sinking liner, you know? Or, if they do, no one made t-shirts about it.

How strong is Tyler Soderstrom? Well, watch this swing:

I’m sure you’ve heard of taking what the pitcher gives you, going to the opposite field when the ball is away rather than trying to pull it. I’m fairly certain that the people giving that advice don’t mean that you should flick your wrists and smash the ball over the fence at 100 miles an hour, though.

I gave you that GIF to start things off because the casual power shocked me when I saw it. That swing didn’t look particularly vicious, but it was. The speed of an individual swing doesn’t tell us that much about a player, but that one was 77.4 mph, and that’s understating it. Swings speed up as they lengthen, with speed measured at the point of contact. The point of contact on that ball was deep – that’s how you go to the opposite field – which means less swing length and thus less swing speed.

That might be Soderstrom’s most impressive home run, but it’s not emblematic of how he’s been succeeding in 2025. And oh, has he been succeeding! He’s already cranked six homers en route to a .378/.440/.822 line; he’s two-thirds of the way to matching his nine homers from last year in a quarter of the plate appearances. And last year wasn’t even a low bar to clear; he posted a 114 wRC+ with excellent peripherals.

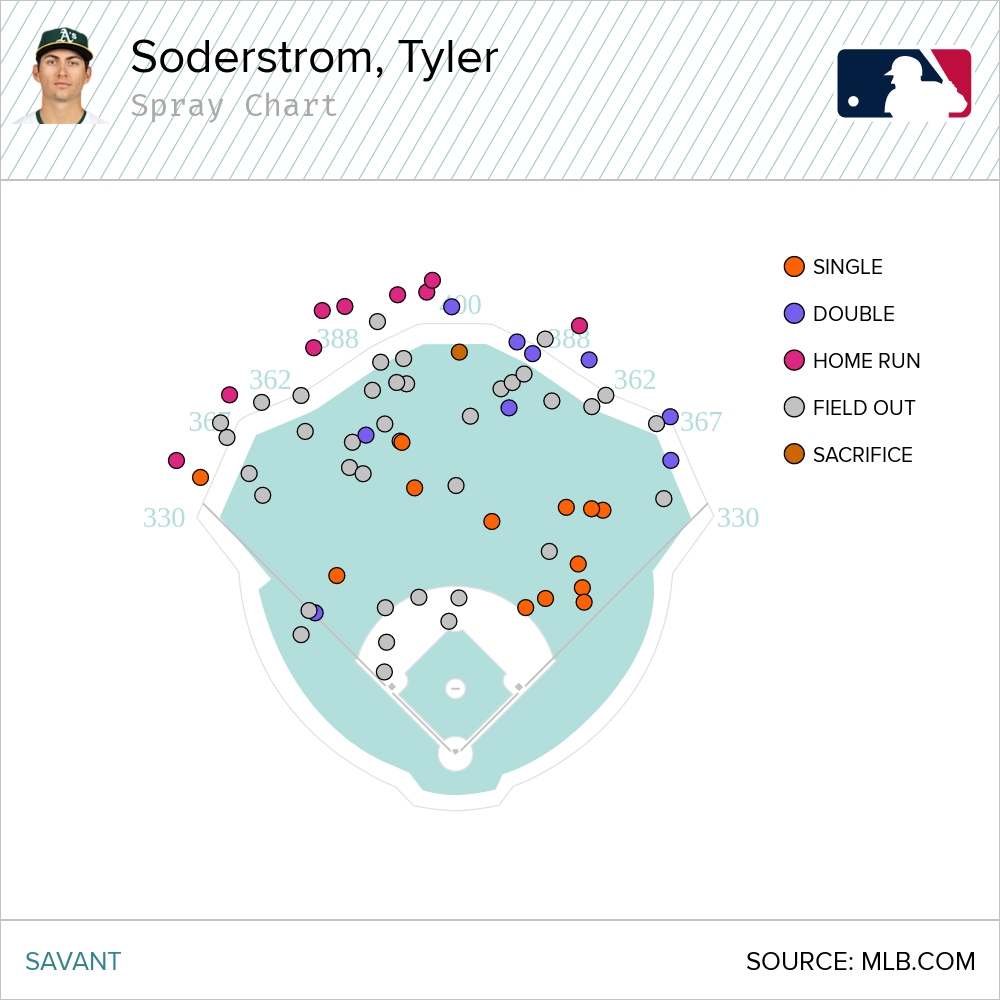

What’s changed this year? Well, small sample size is Soderstrom’s friend, for one thing. He probably won’t keep turning half of his fly balls into home runs, what with this being major league baseball instead of slow pitch softball. But there’s absolutely something new with him this season. Take a look at the locations of every ball Soderstrom hit in the air in 2024:

It’s easy to imagine the approach that leads to this kind of spray pattern. The best-struck batted balls are to center and left center, leading to most of his home runs coming in those areas. There’s a pile of ripped singles in right field, every one a line drive. In other words, he was hitting the ball low and hard to the pull side, and high and hard to the opposite field.

It’s pretty easy to understand why you wouldn’t want that mix of batted balls. Low and hard works better to center field, because it’s hard to hit the ball out of the park there. High and hard works better down the lines, but given that it’s quite difficult to hit the ball high and hard the other way, the big gap in Soderstrom’s production was not enough pulled fly balls. You can be as strong as you want; it’s hard to excel when you hit your fly balls to the biggest part of the stadium.

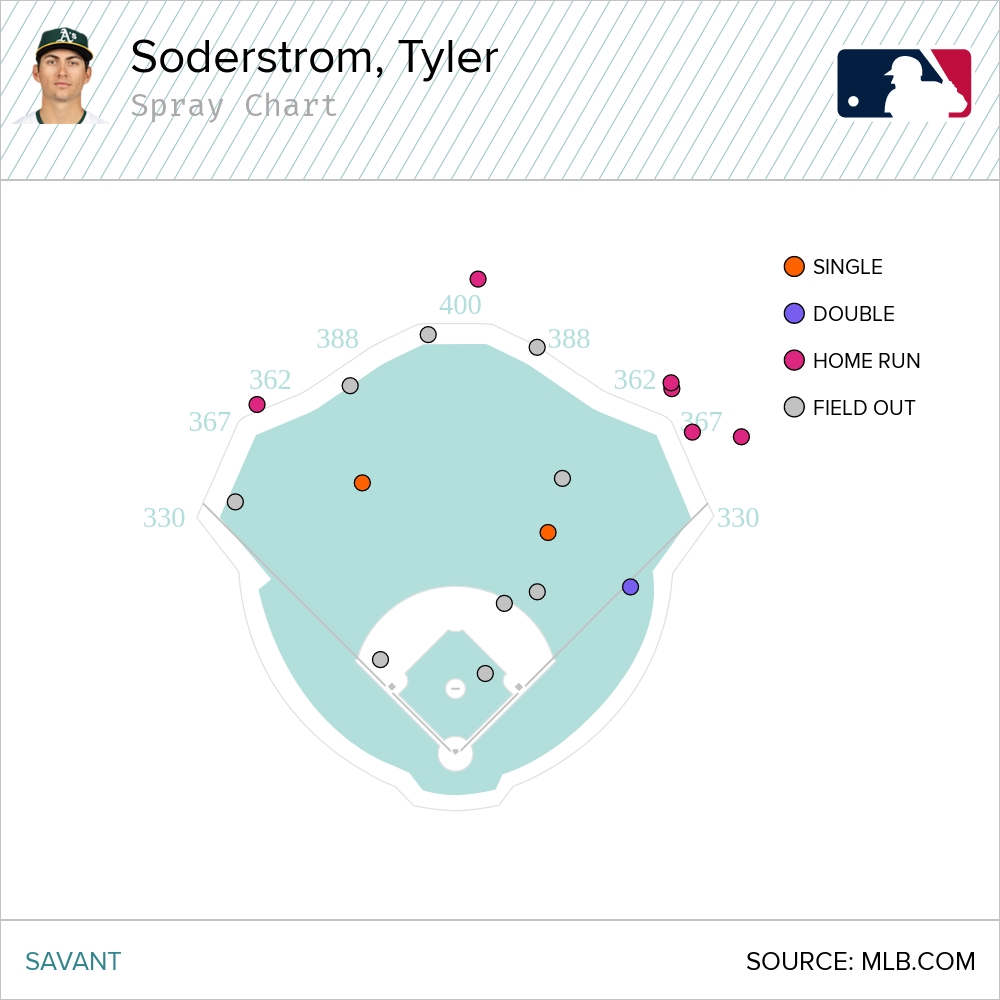

Now, I showed you an opposite field home run to start this article, but that’s not really what Soderstrom has been about so far in 2025:

Rather than peppering the opposite field gap, Soderstrom is lifting and pulling. On aerial contact, his pull rate is up from 24.3% to 50%. Limit it to fly balls specifically, and it’s up from 17.8% to 41.7%. League average for all aerial contact is 31%, and 26% for fly balls in particular. Take huge grains of salt with all of this, because of the limited sample size, but it doesn’t take an aerodynamics PhD to understand that this change has helped him unlock his colossal power.

How do you hit the ball to the pull side? There’s no one way, but as a broad rule, inside pitches are easier to pull and outside pitches are easier to hit the other way. That’s what Soderstrom is doing. He’s going after fastballs on the inner half this year and taking fastballs on the outside edge instead of trying to punch them the other way. His swing rate on outside fastballs is down by 15 percentage points, while his swing rate on inside fastballs has increased.

Could all of this be an early-season mirage? Unquestionably. But I’m willing to intuit real intent here, because the magnitude of the change is enormous. Here it is in grid form:

Fastball Swing% By Location

| Location | 2024 | 2025 |

|---|---|---|

| Inside | 45.3% | 52.3% |

| Outside | 56.2% | 37.8% |

I drew a line down the center of the plate and put all fastballs into those two buckets: inside the midline or outside of it. Soderstrom hasn’t just changed his swing rate or gotten a few extra fastballs inside; he’s changed his behavior in the two zones in opposite directions. That change makes perfect sense; Soderstrom has performed poorly throughout his career when he swings at fastballs away, and well when he swings at fastballs in. He’s just aligning his swing decisions to better match where he’s at his best.

Now that Soderstrom has made this change, pitchers will surely try to adapt to his new plan. There are two obvious counters: Work the outside of the plate with fastballs that Soderstrom is trying his best not to swing at, or pair secondary pitches with inside fastballs to entice bad swings. That means back foot sliders from righties, basically. If a right-handed pitcher aims a fastball and a slider at the same point on the inner part of the plate, the fastball will stay mostly true while the slider breaks toward a left-handed hitter.

Again, it’s still early days, but Soderstrom has been attacking breaking balls that finish inside far more than in past years. His chase rate on breaking balls off the inside part of the plate has roughly doubled from his previous major league numbers. If you’re hunting something inside, this curveball from Bryce Miller looks quite tempting:

And looking for a fastball to drive might make it harder to lay off an inside slider, even on a 3-0 count:

It’s cool to see the effects of an approach change reflected in so many different parts of Soderstrom’s game. Looking inside for fastballs has changed his batted ball quality, but just as importantly, it’s changed which pitches are most effective at causing him to chase. He’s chasing those back foot breakers at nearly double his career rate despite lowering his chase rate on every other pitch/location combination.

That’s the beauty of baseball – Soderstrom has made a change that unlocked the massive power he’s always shown but rarely tapped into. That change has completely altered the best way to pitch to him – new hot spots, new weaknesses, the whole nine yards. Pitchers don’t sit still while hitters change; they get to make adjustments too. Soderstrom might be able to make his own counter-adjustments, of course. It helps that he has enough raw power that he can still hit home runs to the opposite field even when that’s not his goal.

So, to put it another way: No, it doesn’t matter very much that Soderstrom has a 260 wRC+ 12 games into the season. But it does matter how he’s doing it – and he’s doing it by changing his process for the better. That’s very exciting for Soderstrom’s future and for an A’s lineup that needs as many good young hitters as it can get.

Note: All statistics are current through games of April 8.

Content Source: blogs.fangraphs.com