Welcome to another edition of Five Things I Liked (Or Didn’t Like) In Baseball This Week. I was at a wedding this past weekend, a generally fun event for a baseball writer. That’s because strangers ask me what I do, and then I get to say, “I’m a baseball writer.” That plays a lot better than, “I work in accounting/finance/tech,” no offense to any of you in those fine fields. But this weekend, someone inquired deeper. “Oh, like sabermetric stuff?” “Yeah! Kind of. Also I make GIFs of dumb and/or weird plays. And bunts, lots of bunts.” Yes, it’s a strange job being a baseball writer, but also a delightful one, and this week delivered whimsy and awe in equal amounts. So unlike guests milling around at a wedding, let’s get straight to the point – after the customary nod to Zach Lowe of The Ringer for the inspiration for this article format.

1. Not Reaching Home

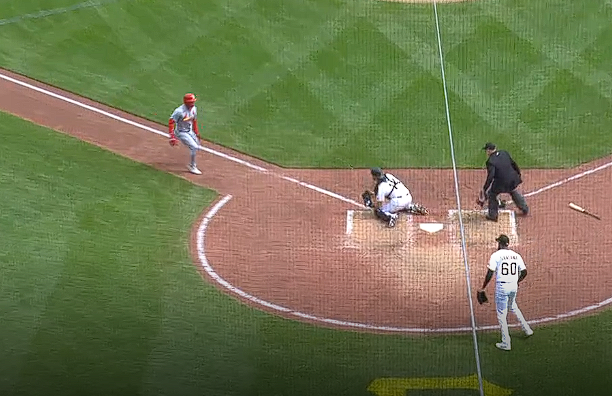

The third time a runner was tagged out at the plate in Wednesday’s Cardinals-Pirates clash came at a pivotal moment. Locked in a scoreless tie in the bottom of the 11th, Pittsburgh finally looked like it would break through when Joey Bart singled to right. But, well:

That was a good throw by Lars Nootbaar and a clean catch by Pedro Pagés, and that combination turned a close play into a gimme. I mean, how often are you going to be safe when the catcher already has the ball in his glove and you’re here:

Hey, doesn’t Alexander Canario’s position seem strange to you? It sure did to me – and was noted by both announcing crews during the replay. I don’t think he would have been safe anyway, but he definitely added a few feet to his route:

Plays like that happen from time to time in baseball. I don’t think sending Canario was the obvious choice, but it was defensible. Ending the game then and there, with one of the best strikeout pitchers in baseball on the mound, is enticing. And really, you can’t plan on the throw being that good. Nootbaar, who has a strong arm, just dropped in a laser beam:

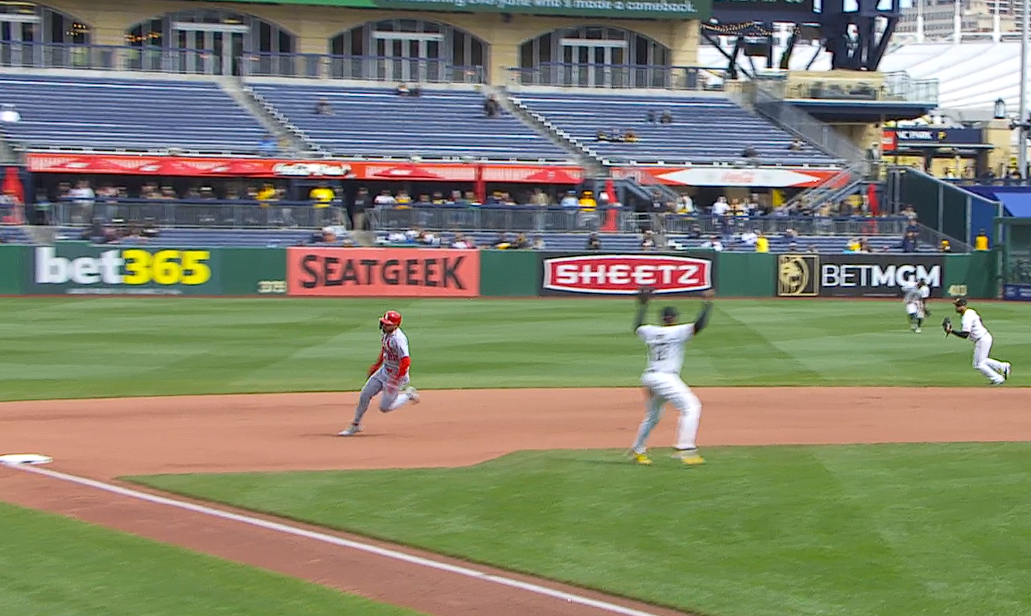

So that one? Pretty reasonable. But the second time someone got tagged out at the plate in this game? That one was a doozy. The Cardinals inserted one of their fastest players, Michael Siani, as the automatic runner in the top of the 10th inning. Pagés lashed a single to shallow left field to lead off the frame. Let’s just say it didn’t end well for St. Louis:

I didn’t spit out my drink when I was watching, but that’s only because I didn’t have a drink. Seriously, here’s where Siani was when Bart secured the ball in his glove:

Again, probably not gonna be safe on that one, and this was a meaningfully worse decision than the Canario play. There were no outs, and the run wouldn’t have ended the game; you’re always trying to score two runs in extra innings as the away team, which makes sending a runner here less valuable even if it works out. And how likely was it to work out? Not very! Here’s when Tommy Pham had the ball in his glove in left:

You’d want the runner to be safe about 90% of the time to send him in that spot, and again, did you see where Siani was when Pham retrieved the ball? I don’t care if Usain Bolt was rounding third; the math just doesn’t add up when the fielder is so close and in possession of the ball so early. Siani would have been out with even an average throw, but Pham’s was excellent:

Here’s the kicker: That wasn’t the worst out that a Cardinal made at home plate in this game. No, that’d be the first time a runner got tagged out at home in this game. There was no throw necessary for this one:

Honestly, I’m not even mad, just in disbelief. Was that poor baserunning by Thomas Saggese? Indubitably. If he continued into the pile-up of Bart and Endy Rodríguez, he would have scored for sure, because lying in the basepath after you’ve “made an attempt to field a ball and missed,” to quote the rulebook, is no defense against obstruction. Saggese had the right of way as soon as the ball clanked off Rodríguez’s glove. Even if he didn’t want to step on anyone, he could’ve veered into the foul side of the basepath, which was wide open. But Saggese didn’t do either of those things; he slowed nearly to a stop and then turned into traffic:

You can see him watching Ke’Bryan Hayes and trying to figure out how to squeeze through to home plate. But that’s not good baserunning; good baserunning is taking your path and continuing into the fallen fielders for an automatic run via obstruction, or at the very least, deviating from your path to avoid the fielder closest to the ball. Instead, Saggese looked like me in a grocery store aisle – “excuse me, sorry, would you mind if I – oh, never mind, I’ll wait…”

Don’t lose sight of how good Hayes was here, though. One of the best defenders in all of baseball lived up to his reputation. He kept his eyes on the play the entire time even though he wasn’t directly involved, and I love how he played the ball after it came free. He didn’t dive for it, because the momentum of doing so would’ve taken him out of the play. He also understood that if he’d slowed down, Saggese would have done so as well, because of where he was standing — and Hayes never lost sight of the runner. When he scooped up the ball, he already had both feet planted, and he lunged to cover the plate immediately afterward. He kept his cool while everyone else lost theirs – and ended up saving the game in a 2-1 Pirates victory in 13 innings.

2. Saving Your Closer

Speaking of pitchers duels, the Mariners and Astros went into the ninth inning Tuesday night locked in a 1-1 tie. Seattle closer Andrés Muñoz was warming in the bullpen, but manager Dan Wilson eschewed him in favor of Carlos Vargas, a middle reliever who entered with only 11 1/3 innings in his major league career and a 4.98 FIP in Triple-A in 2024.

I loved it! I wrote about the correct time to save your closer when the zombie runner was first introduced, and this tactic makes perfect sense to me. Muñoz’s great skill is missing bats; he has a career 34.3% strikeout rate. Strikeouts are just the same as any old out with the bases empty, but with a runner aboard, particularly if the runner isn’t on first, strikeouts go up in relative value by quite a bit. Retiring a batter with no chance of advancement is a big deal, and never bigger than when there’s a runner on second with no outs or a runner on third with one out, two positions that come up quite frequently in extras.

Even a bad pitcher will throw a scoreless inning more often than not if a runner doesn’t start the inning in scoring position. That made the ninth a better time to use Vargas – and he did exactly what Wilson had hoped, retiring the side in order. That preserved Muñoz for the 10th inning, and that’s precisely how things worked out after Seattle’s hitters didn’t score in the bottom of the ninth. Muñoz came in and blew away the first batter he saw, then worked through the rest of the inning without allowing a run. Just like Wilson drew it up.

On the other side of the field, manager Joe Espada and the Astros used their own extra innings plan. Closer Josh Hader came out to pitch the bottom of the ninth and took care of business, with two strikeouts in a perfect inning. But Espada wasn’t making a mistake by not saving his closer – he knew his closer could pitch multiple innings. Hader came back out for the 10th and looked as good as ever, notching two more strikeouts en route to another clean frame.

The two methods were a good reminder that there’s never just one way to do things in baseball. You can tinker around with your existing players, trying to squeeze out an extra few percentage points of win probability – or you can just use one of the best relievers in the game for multiple innings and avoid answering the question at all. Houston won 2-1 in 12, but both teams expertly used their bullpen in their own specific way.

3. Valiant Efforts

That game was so good that I couldn’t limit it to just one item. I mentioned that Muñoz pitched a scoreless 10th, but he was only able to do so thanks to a heroic play from Ryan Bliss. With two outs, Jose Altuve stroked a grounder that briefly looked like it would be a routine out. Then it hit second base:

Oh my goodness, what a play. Look at him transition from getting low to field a grounder into leaping to snag a carom:

I would say that you should try making this move at home to understand how much coordination it requires, but you’d probably hurt yourself. By the time Bliss realized that he needed to go high to grab the ball, his left foot was barely on the ground. That meant he had to gather all his weight on his right leg and make a one-footed sideways jump to have a play on the ball. Even then, it was at the very edge of his catch radius, which made for a tough play. The reverse angle shows how little time he had to decide what to do:

That’s just spectacular, and it saved the game. The baserunner would have scored if Bliss didn’t keep the ball in the infield, and the Mariners weren’t likely to score against Hader in the bottom half. Sure, that play didn’t result in an out, but it was one of the best defensive highlights I saw all week anyway.

The Mariners weren’t done showing off their defensive skills, though. Houston threatened again immediately, loading the bases with one out in the top of the 11th inning. Then Dylan Moore briefly entered the matrix:

Uh, what?! We’re gonna have to see that one again:

Just your average glove deflection, barehanded scoop, plant on the bag and side-arm throw off balance to hit your first baseman on the fly with no margin for error. Oh yeah, and all of that off the wrong foot thanks to where the play occurred. That grounder was an absolute missile, 108 mph off the bat, and it’s no surprise that it handcuffed Moore. But instead of giving up on it or taking a single out, he kept his eyes on the prize. I mean that literally. Watch him keep his head down and secure the ball even as he starts to dream of a double play:

I have no notes – that was perfect. Neither of those gems ended up mattering, because the Mariners couldn’t score and the Astros eventually broke through. But that doesn’t make either play less spectacular. Watch some Mariners games if you get a chance. The runs might be hard to come by, but the highlights aren’t.

4. Full Layouts

Derek Hill is the platonic ideal of a journeyman outfielder. He can play all three positions, though he’s a natural center fielder. He can flat out fly, both on the basepaths and in the field. Can he hit? Not really! But between pinch running, getting in as a defensive replacement, and filling in for the starters when they get their occasional days off, Hill could be a serviceable fourth or fifth outfielder for many teams, a classic fringey option – which explains why he played for the Rangers, Giants, and Marlins in 2024 after a series of waiver claims.

This year, he’s in a center field timeshare with Dane Myers in Miami. He’s off to the best offensive start of his career, although that’s damning with faint praise: He’s striking out more than a third of the time and barely walking, but a .429 BABIP has propelled him to a 126 wRC+ through 30 plate appearances. But this item isn’t about his long-term place on the Marlins. It’s about the skills that keep landing him major league jobs despite his career .280 OBP. Skills like this:

Oh. My. Goodness. It’s a shame that the FAA has gone through so many layoffs this year, because if they had the bandwidth, I assume they would have asked Hill for a flight plan and tail number when he took off there.

Hill was playing Tyrone Taylor extremely shallow, and also shaded to right. How shallow? He was 290 feet from home plate when Taylor made contact. Average center field depth is 322 feet; the Marlins have played their center fielders at 316 feet on average this year. So Hill was about as far away from the ball as is feasible, and to make matters worse, the ball was tailing away and headed for the warning track. This is a play that most outfielders wouldn’t even attempt; you have a much better chance of playing a carom than making the catch and holding onto the ball.

Even the elements were working against Hill. The start time of this game got moved because of unseasonable cold; it was in the low 40s, with strong winds producing gusts above 40 mph. That’s both bad weather for tracking a ball in flight and tough weather for diving onto a hard-packed dirt surface. This angle made me wince in pain even as I nodded in appreciation:

I’m not sure what else to say about this one, so I’ll just leave it to Ronny Henriquez, who got bailed out on a ball that he surely never expected to come anywhere near a fielder’s glove:

And fine, with this spectacular image of Hill letting everyone know that he caught it:

5. Grand Openings and Grand Closings

This wasn’t the first or last week of the year, but there were still some momentous beginnings and endings. First, J.C. Escarra got his first major league hit in his first major league start:

Calling Escarra, who turns 30 in 13 days, a Cinderella story doesn’t do him justice. After flaming out as a 15th-round pick, he spent two years bouncing through Indy ball and the Mexican League; if you’ve played for the Gastonia Honey Hunters and also the Algodoneros de Union Laguna, you must really love the game of baseball. Escarra could have quit; he was driving for Uber and substitute teaching to make ends meet. But he didn’t, and after he latched on with the Yankees in 2024, he put together a solid season across two levels of the minors.

When the Yankees traded Jose Trevino to the Reds in December and then exited free agency without securing a veteran backup catcher, Escarra’s road to the majors opened up. He seized the opportunity, and he’s living out his major league dream. Look at how happy he was after recording that double:

Also happy: Mike Yastrzemski, though for a completely different reason. Yaz has a journeyman story of his own, though it’s not quite as dramatic as Escarra’s. But now he’s ensconced in right field as a platoon bat for the Giants. He’s a great fit for Oracle Park, with the instincts and range to cover Triples Alley and a lefty power stroke built to pepper the right field wall. On Wednesday, he capped a furious comeback with one of the rare delights of San Francisco baseball, a splash walk-off:

Plenty of stadiums have their own quirky home run options. You could hit it off the apple in Queens, off the warehouse in San Diego, or into the pool in Phoenix. You could launch one over the Monster at Fenway or into Big Mac Land at Busch. But splash hits into McCovey Cove are my personal favorite, and not just because I live here now. The kayakers and gawkers, combined with the memories of seeing Barry Bonds treat it like his own personal water hazard, have always delighted me. The combination of the enormous wall and reachable-but-still-challenging distance makes for great optics, too: If you hit a splash home run, it’s almost always a no doubter, which means that every splash hit comes with the celebration that accompanies a clear home run. Yastrzemski knew that ball was gone right off the bat, even before the fans understood how hard he’d hit it:

What a way to end a game. And what a way to start a career for Escarra. More of both, please.

Content Source: blogs.fangraphs.com