This year, Josh Bell returned to Washington with a new goal in mind. “What this team needs is slug,” he told reporters during a Zoom call when he signed back in January. He explained that although he’d always prided himself on making contact and avoiding strikeouts – Bell’s career strikeout rate is 14% below the league average and his slugging percentage is 5% above it – he was finally ready to make use of his 6’3” frame and trade contact for power:

That’s kind of in my DNA, but understanding MVPs the last few years, they hit 40-plus homers and they might strike out 150-plus times, but that doesn’t get talked about. The slug is the most important thing. That’s where WAR is. That’s what wins games… I have a big frame, and I should probably hit more than 19 home runs a season. Hopefully, a year from now I can be looking back on a season where I had 40-plus and break my own records for slug in a season. That’s the goal.

Bell came into the season with a more upright stance, a slightly higher leg kick, and a new mission. “I feel like I’m not afraid to strikeout more if it means less groundballs,” he said in February. “I know when I’m at my best, I don’t hit the ball on the ground. I strike out a little bit more. So if I can take one and get rid of the other, then I’ll be in a good place and the average should stay the same or go up. Time will tell.”

I bring all this up because Bell has seen a huge change in his batted balls this season, but it’s very definitely not the change he hoped to see. So far this season, he’s running a .173 ISO, a bit down from his career mark, but more or less in line with what he’s done for the last several years. His hard-hit rate and exit velocity are nearly identical to last season’s marks. So in terms of both results and raw contact quality, he’s not more powerful, but he’s not less powerful either. The experiment may have failed, but it didn’t blow up the laboratory.

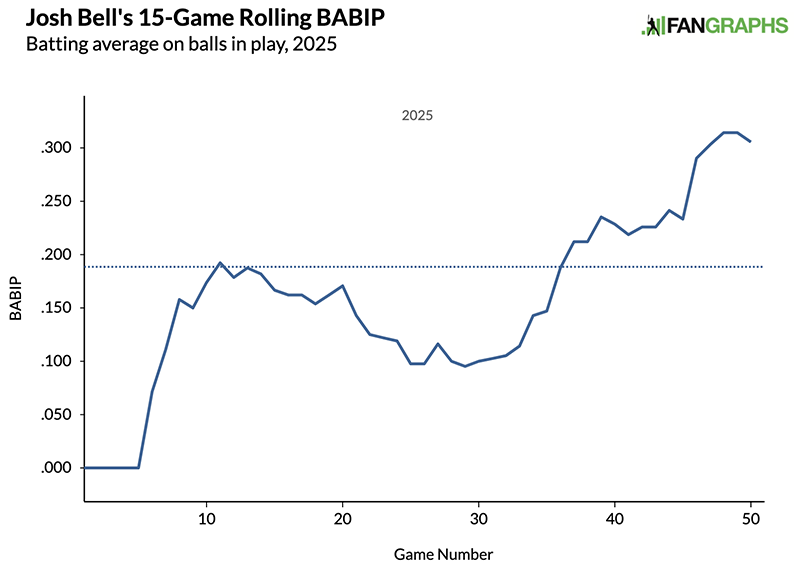

The thing is, the laboratory did blow up. Beakers and Bunsen burners and those little sparker thingies you use to light the Bunsen burners are raining down across the entire Eastern Seaboard, because Bell wasn’t just talking about isolated power. He was talking about slugging, and he’s currently running a .358 slugging percentage. That’s the lowest of his entire career, and 67 points off his 2024 mark. How did he lose so much slug while his contact quality and ISO stayed pretty much the same? The answer is the reason we’re here. Bell is currently running a .189 BABIP. That’s bad by Bell’s standards. He’s a big, slow, would-be power guy, but he’s never run terrible BABIPs. His career .284 mark is good for a 95 BABIP+, below average, but not disastrously so. In case you didn’t major in subtraction, that means Bell is currently 95 points below his career mark.

That’s also bad by any standard, ever. It’s the lowest BABIP among qualified players by 28 points. I pulled the BABIP of every player in AL/NL history who made at least 400 plate appearances in a season. Bell is on pace to run the second-lowest BABIP of all time, not far above second baseman Joe Gerhardt, who batted .155 with a .176 BABIP for the New York Giants in 1885. Luckily, what Gerhardt lacked as a hitter, he more than made up for with his mustache.

The bottom of the list is actually quite fun. It’s got lots of hitters who just happened to have terrible years, but it’s also full of home run-hitting specialists like Pete Alonso, Kyle Schwarber, Dave Kingman, Mark McGwire, and even Roger Maris in his record-setting 1961 season. When every ball you hit hard goes out of the ballpark, you’ll run a rock-bottom BABIP, because your balls in play are just the weakly hit balls that remain.

I feel fairly confident that Gerhardt’s numbers are incomplete – it’s hard to trust the scoring in a season that occurred three years before the ballpoint pen was invented – so if we limit ourselves to qualified players from the modern era, Bell finds himself seven points below the .196 record set by Toronto’s Aaron Hill in 2010. If we adjust for the league average, Bell has a BAPIP+ of 64, well below the 66 put up by Hill and Cleveland’s Willie Kirkland in 1962.

As always, we should note that we’re only a third of the way through the season. BABIP is, by definition, extremely dependent on luck, so it’s very unlikely that Bell will actually set this record. We’d expect any player running a BABIP that low to regress to the mean, and Bell began doing so a couple weeks ago.

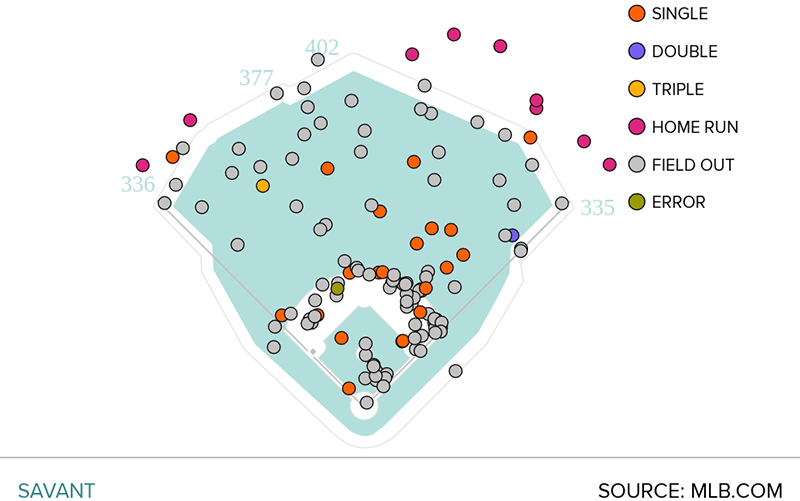

All the same, it’s hard to imagine things getting this bad for no reason whatsoever. It’s not just luck, and there are plenty of real differences in Bell’s game. He has dropped his goundball-to-fly-ball rate to 1.22, down from 1.50 last season and the lowest he’s put up since 2019, the best campaign of his career. His 38.2% fly ball rate is the highest of his career, and largely because a career-high 18.3% of his balls in play have been pulled in the air, 18% of his fly balls have gone for home runs. That’s not a huge number, but it’s his highest in years and it puts him in the 79th percentile among qualified players. So in a certain way, Bell really has succeeded at his goal. At least from the left side, Bell is lifting the ball in the air and hitting home runs.

Statcast’s bat tracking numbers show that from the left side of the plate, Bell has indeed looked a bit different. Although his swing path is angled roughly the same as it was the last two seasons, he’s meeting the ball farther out in front of the plate – or, more accurately, he’s not meeting the ball as far behind the plate as he used to – helping him record a higher bat speed than he did in 2024 (though not 2023), and giving him a slightly steeper attack angle, allowing him to lift the ball more.

Even so, that hasn’t helped Bell hit the ball in the air more, or at least not yet. This season, 44.5% of his batted balls from the left side have been fly balls and line drives, his lowest mark since 2022. However, when he has hit the ball in the air from the left side, he’s been really impressive; his 98.3-mph average exit velocity is the highest of his career by a wide margin — but he’s not seeing results just yet. He’s hitting deep fly balls that get caught on or before the warning track, but fewer line drives that fall in for singles or end up in the gap for doubles. Bell has just one double and one triple this season (and the triple was an absolute gift that should’ve been a single). His slug is coming almost entirely from homers and singles.

Some of this may just be bad luck. Bell will likely hit more line drives or see a few more fly balls make it past the warning track as the weather heats up. However, although the bat tracking numbers don’t look all that different, it does seem like selling out for pull-side power has affected his swing. He’s popping the ball up more. When he hits the ball on the ground from the left side, he’s running the highest pull rate, but the lowest launch angle, exit velocity, and hard-hit rate of his career. Clearly, his swing isn’t as geared for groundballs anymore, but he’s still hitting a lot of them, to a worse spot on the field, and the results have been very bad.

To recap, from the left side, Bell is pulling the ball in the air more, just as he’d hoped. But the result has been a lot of fly ball outs and popups. Moreover, he’s also pulling the ball on the ground more, resulting in tons of weak outs to first and second. Bell’s .208 BABIP from the left side is more than 80 points lower than it’s been in any previous season.

When Bell is batting from the right side, the opposite has happened. His bat speed is up some, but he’s making contact deeper than ever and his bat is flatter than ever. He’s lifting the ball at roughly the same rate he has over the last few years, but those air balls aren’t not falling because he’s hitting them more weakly than ever. His BABIP from the right side is .095, the worst of his career by more than 110 points.

The spray chart says it all here. Bell is hitting more fly balls and fewer groundballs. But he’s not hitting the ball much harder, so a lot of those fly balls are just long outs. He’s also not squaring the ball up well, which means fewer line drives and a lot more easy groundball outs to the right side.

The new bat tracking data has really emphasized the extent to which hitting is about trade-offs. Sure, the best players in the game are the ones who can do lots of things well. They recognize pitches well, which allows them to get in the best position to hit the ball. They’re flexible and strong, which allows them to damage pitches over a large area of the strike zone. And they’ve got the kinesthetic intelligence to figure out how to adjust their swings without leaking bat speed. But that’s a rare collection of gifts reserved for the very best in the world. Most hitters can’t do everything. They’re constantly trying to figure out which approach, which stance, which stride, which load, which bat path will allow them to make the most of the gifts they have while exposing as few of their weaknesses as possible.

Bell deserves a huge amount of credit for deciding to reinvent himself at age 32, with nine big league seasons under his belt. I’m not even sure I’m ready to conclude that this experiment is a failure just yet. Bell’s new approach has exposed some new flaws, but it’s still early on. He won’t stay this unlucky, and he’ll probably improve as he gets more experience with this approach. “It’s not going to come in one night or one week,” he said a few weeks ago. “It’s stacking at-bats and stacking series and stacking months at this point to try to make up for some of the ruts that I’ve been in the last few weeks.” He took a first step at that over the weekend. In his past five games, he’s batting .429 with three homers, and he’s raised his BABIP by 16 points. When I pitched this article, he was below old Joe Gerhardt, and his BABIP+ was at a mere 60. When you’re starting out this low, there’s only one direction left to go.

However things shake out, Bell is unlikely to set a new record. If we assume that he plays the rest of the season with the same rate of plate appearances per game, he’d only have to post a .200 BABIP the rest of the way in order to avoid breaking Hill’s record. That’s an incredibly low number. Bell’s the only qualified player under .217 right now! Moreover, if he does keep running such an abysmal BABIP, even for a team as hopeless as the Nationals, he’s probably going to lose some playing time, which could keep him from qualifying. That’s why it’s so hard to set the bad records. If you keep playing badly, you won’t keep playing.

You could even argue that Bell hasn’t gone far enough with this new approach. His batting stance doesn’t look all that different. His contact and strikeout rates aren’t that far from his career marks, and as I mentioned earlier, his bat tracking numbers don’t show a much steeper swing at all. He’s also been much less aggressive, running his lowest zone-swing rate in years, and the bat tracking metrics show that he’s meeting the ball deeper than 91% of the batters in the league. That’s not what it looks like when someone’s attacking the ball and looking to do damage. Maybe Bell will decide to abandon this experiment and go back to doing what he does best. After such a rough start, it would be hard to blame him. But assuming his batted ball luck continues to rebound, it might not be that harmful to continue the experiment.

Content Source: blogs.fangraphs.com