I never thought I’d get to use the transit method. If that phrase rings a bell but you can’t quite place it, let me remind you about NASA’s Kepler space telescope, which spent nine years pointed out into space, observing stars. By measuring tiny dips in the brightness of those stars, scientists were able to detect the existence of thousands upon thousands of planets that orbited them. Those exoplanets blocked out some of the light when their orbit brought them between their star and Earth, and Kepler was attuned to interpret the minuscule effect of those shadows. Anyway, this is as close as I’ll ever come.

It happened in Seattle on Wednesday, and it started in the bottom of the seventh inning. The score was knotted at three at the beginning of the frame, but the Mariners quickly broke things wide open. J.P. Crawford knocked in two runs with a single past the third baseman, then Julio Rodríguez knocked in Crawford with a double to the deepest part of the ballpark. That brought Cal Raleigh to the plate with Rodríguez, briefly, on second. In the dugout, tuckered out from his 270-foot journey, Crawford did exactly what a high-performance athlete is supposed to do. He focused on recovery.

Raleigh took a Reid Detmers curve for a ball, then another for a strike. Rodríguez took off as soon as Detmers raised his right foot for the 1-1 pitch. The slider hit the outside corner and Raleigh was out in front of it, chopping it down toward the third baseman. Or rather, toward where third baseman Luis Rengifo would have been standing were he not covering third base. The steal attempt forced him over to the bag and he watched helplessly as the world’s easiest chopper floated right toward the vacancy he’d created. But that vacancy was soon to be filled. Rodríguez bore down on the base, putting him on a collision course with the ball. Or not.

I’ve never seen a play like this in my life. I’m not sure anybody has seen this particular play before. Rodríguez seemed to dive directly under the baseball. Did he know it was coming? Was this a masterful evasion that he was able to tie in with a perfect steal of third base? Let’s go to the tape.

Nope. It was not a masterful evasion. Rodríguez had his head down the whole way. He never peeked at the ball and had no idea it was coming. The immaculate timing was pure coincidence. I imagine that sometimes this is what it feels like to be a professional athlete. You’re just doing your thing. It feels totally normal to you. It’s what you do. Meanwhile, everyone around you, a whole stadium full of people there just to see you, thinks what you did was so mind-bendingly incredible that they question their grasp on reality. They’ll tell their grandkids about this spectacular moment. Meanwhile, the third base coach is yelling at you, so you have to get back up and run 90 more feet.

Last year, I wrote about the very opposite of this play. Jose Altuve was on second base. He wasn’t stealing. Alex Bregman hit a weak groundball between short and third, and Altuve watched the ball the whole way. He slowed down and spread his arms, carefully chopping his steps seemingly in preparation for some sort of daredevil acrobatic wizardry that would leave the defenders so dazzled that they’d stand there slack-jawed as the ball trickled between them. And then he just ran right into the ball. Like, directly into the ball. It bounced off both his shins. He was out. The inning was over. I wrote a whole poem about it and about all the other ways that we humans tend to wind up for something really big only to end up doing nothing at all.

After watching Rodríguez’s dive from every angle I could get my hands on, I asked the obvious question. How close did the ball really come to hitting him? He was moving so fast that it was hard to get a read on exactly how close he was to it. Maybe it looked closer than it was, which would be a shame. The wonder of the play is that it really does look like he’s bearing down on third base like a freight train while managing to come within micrometers of the ball. The television broadcasts only showed the play from three angles, and all three were more or less from behind home plate, so I couldn’t compare them to triangulate the actual location of the ball when it passed Rodríguez. What I could do was use the shadows. I took the best replay and went through it frame by frame, highlighting the shadow of the ball.

Did you lose the shadow for a minute? Your eyes aren’t playing tricks on you. As the ball and Rodríguez reach the same airspace, the shadow on the ground disappears. Rodríguez is blocking it entirely. If you watch very carefully, you’ll see the shadow climb up his ribs and travel across his back.

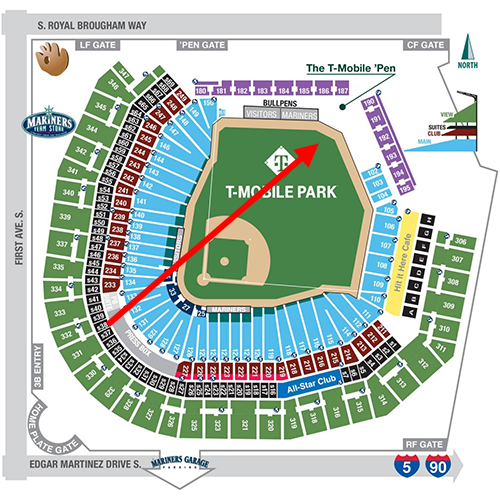

It certainly looked like the ball went right over Rodríguez, but let’s dig into it. The play took place two hours and 22 seconds after the 1:10 PM first pitch. According to the Navy’s Astronomical Applications Department, at 3:10 PM, the altitude of the sun at T-Mobile Park was 48.9 degrees, roughly two hours past its maximum height of 57.8 degrees. Its azimuth was 229 degrees. In other words, at the time of the play, shadows were short because the sun was still very high in the sky, and they fell at nearly the exact same angle as the path between home plate and the pitcher’s mound.

The big red arrow is the direction of the sun, and thus the direction of the shadows. Knowing all that, let’s slow this clip down even further so we can pinpoint the exact moment when the ball was directly over the diving Rodríguez. As you watch, try to draw a line in your mind from the ball to the shadow, so you can see when it’s actually closest to him.

To my eye, the frame below is the one in which the ball is closest to Rodríguez, and when they’re at the same depth in the shot. Given the angle of the sun, I picked it because it’s two frames after the shadow disappears entirely. The shadow is now on the right side of Rodríguez’s back, which we can’t see, meaning that it’s just over the center of his body. Now that we know this is how close the ball came, let’s take a second to acknowledge that it was really, really, really close. It almost got him right in the brain.

From this point, it’s easy. I took this frame and measured the number of pixels in the diameter of the baseball and the number of pixels between the baseball and Rodríguez. We know that the baseball is between 2.865 to 2.944 in diameter, so we have three of our four variables. We can cross-multiply to solve for X, just like we learned in algebra class. (Thanks, Ms. Wilkie!) According to my math, the ball was almost exactly six inches away from Rodríguez’s helmet. Luckily, that’s easy math to check, given that six inches is just about the width of two baseballs.

Yup. The baseball missed the baseball player by two baseballs. What a world.

This was as exact as I could get, and, well, it’s not particularly exact. It’s definitely not the transit method, but I’m going to give myself credit for that anyway, as it is an attempt to determine the path of a sphere through space by observing the starlight it blocks. Then again, exactness is not the point here. The point is to find an excuse to spend some time with a play that nobody, not even Rodríguez, could orchestrate if they tried. We’ve seen what happens when somebody tries. It’s not pretty.

This play could’ve turned out badly, too. In fact, Rodríguez came just six inches from getting knocked on the helmet and being called out. In another world, Rengifo doesn’t try to cover third base, and he’s just standing there waiting for the ball. Rodríguez has to slow down to avoid a collision, so Rengifo tags him out and then nails Raleigh at first for a double play. Either of those plays probably would have been weird enough that I still would’ve ended up writing about them, but I’m glad it went down this way. If it hadn’t, I wouldn’t have gotten to use the transit method.

Content Source: blogs.fangraphs.com