Every year, the Baltimore Orioles turn out a crop of strapping young hitters who just got done obliterating minor league pitching. You’ve probably heard of many of them. Adley Rutschman, Gunnar Henderson, Jackson Holliday, Colton Cowser, Jordan Westburg, Samuel Basallo, the list goes on. All six of those guys will be everyday regulars next year; the only reason they aren’t now is because Rutschman and Westburg are on the IL. But lost in that percolation of prospects is Coby Mayo, whose early major league career hasn’t quite gone as expected. I wondered why – and what Mayo could do to capitalize on his promise.

A year ago, Mayo was comprehensively dominating pitchers meaningfully older than him. He posted a 139 wRC+ in Triple-A at age 22, following up on an equally scintillating 2023 season. He was a preseason Top 100 prospect. His raw power was immediately evident to all observers. He looked like he’d be a key piece of the 2025 Orioles’ playoff run. But that run never materialized, and neither did Mayo’s thumping, mid-lineup offense. Instead, he’s hitting .184/.259/.327 and batting ninth for the last-place Birds.

If you watch Mayo play, one thing jumps off the page: his unconventional uppercut swing. I’m not even quite sure how to describe it, but here’s a video of it at its best:

Swing mechanics aren’t my area of expertise, so I’ll just say it has a little funk to it and move on. The point is that he uses that swing to clobber the ball, and he really does accomplish what he sets out to, bad season notwithstanding. He has elite bat speed, and even in this miserable season, he’s posted good raw power indicators; his EV90, barrel rate, and launch angle suggest that he’s going to be elevating and celebrating plenty over the years to come.

Any Mayo wishcasting has to take that chief strength into account. What’s it going to look like if Coby Mayo is an All-Star? There are probably going to be a lot of home runs and doubles involved, thanks to an absolute mountain of fly balls and line drives. There are going to be strikeouts, too. Look at that swing again. There’s a reason Mayo’s minor league strikeout rate hovered around 25% even while he was posting excellent results.

Great, cool, we can work with that. The “slugger who strikes out a lot” archetype encompasses many of baseball’s best players. Shohei Ohtani, Aaron Judge, and Cal Raleigh are among the game’s top hitters, and they all strike out more than the league average. Throw in Kyle Schwarber, Rafael Devers, and Matt Olson if you’d like. And I could keep going; 16 of the top 30 hitters in baseball this year have a higher-than-average strikeout rate.

If we’re going to make Mayo great while keeping his strikeouts, we’re going to have to do something about the contact quality. It’s one thing to strike out 30% of the time, and another entirely to strike out 30% of the time while hitting a measly .276 with a .490 slug when you put the ball in play. That’s not BABIP, because it counts homers; league average wOBA on contact is around .370, and Mayo clocks in around .325. You can’t be a boom/bust slugger if your contact isn’t booming. Mayo’s top-line data all looks good, but he’s not getting to his best contact often enough to flatter his batting line.

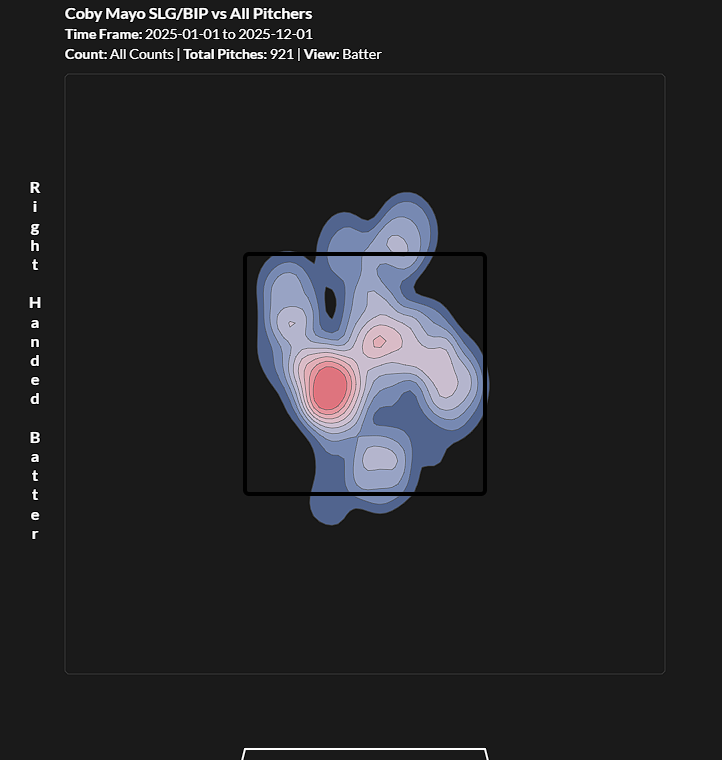

Where does Mayo do damage? Over the heart of the plate, naturally. Here’s a map of his slugging percentage on balls in play based on pitch location:

Sure, sure, seems good. The redder the area, the more power he’s producing, and though there are surely sample size issues given his limited major league playing time, I totally buy the conclusion. Like most players, Mayo does his best work on pitches over the heart of the plate. Slightly less like most players, he likes the ball middle-in. That’s marginally strange for someone with plus power – those guys often like to get extended on middle-away pitches – but he’s quite pull oriented, with not a single one of his seven homers going to the opposite field. Chalk it up to the swing, perhaps, but I think it’s fair to say that someone with his lofted swing, plus bat speed, and pull approach should look to find balls that he can elevate and pull.

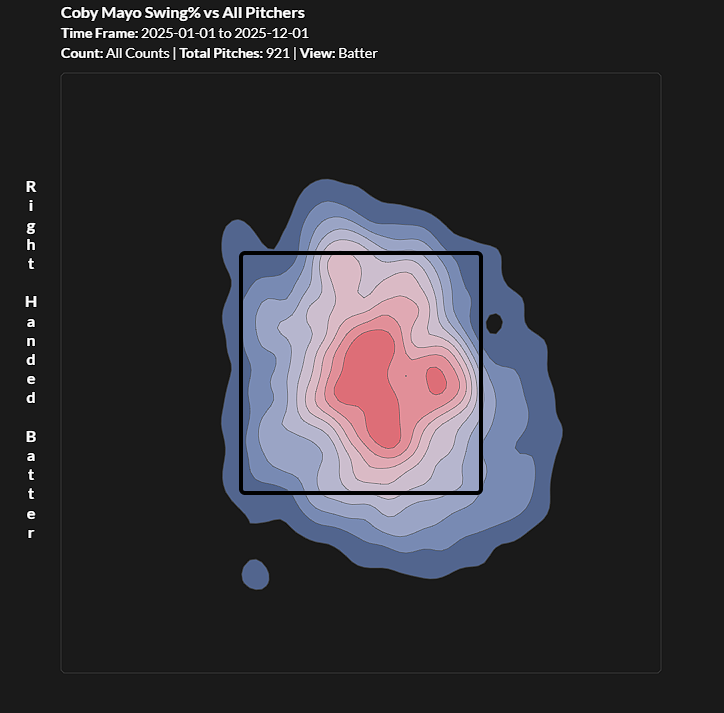

Where does he swing? Middle-away, like most of his high-power brethren:

That looks a lot like any number of other elite sluggers. The problem is that Mayo’s damage on contact doesn’t resemble theirs. Imagine splitting the heart of the plate into two halves, inside and outside. Separate the halves by drawing a line right down the middle of the plate. It’s easy to see which one is more conducive to his plan of accruing extra bases in the air:

Coby Mayo’s Middle-Middle Results, Split in Two

| Split | BA | xBA | SLG | xSLG | wOBACON | xwOBACON | Barrel% | Had Hit% | Launch Angle |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inner Half | .265 | .310 | .529 | .669 | .334 | .410 | 11.8% | 47.1% | 23 |

| Outer Half | .263 | .253 | .474 | .440 | .313 | .294 | 7.9% | 50.0% | 15 |

Now, please don’t take those numbers as conclusive. It’s about 35 batted balls a side, far too few to be a stable measure of his production. But even if the specific numbers are noisy, the shape of the pattern is striking. Whether it’s the swing, the stance, the approach, or something that can’t be boiled down to a simple description, Mayo hasn’t shown the opposite-field barrel skill that is a common result of elite bat speed. Even worse, he has a 43% groundball rate on middle-away pitches, compared to 26.5% on middle-in. Slug is in the air.

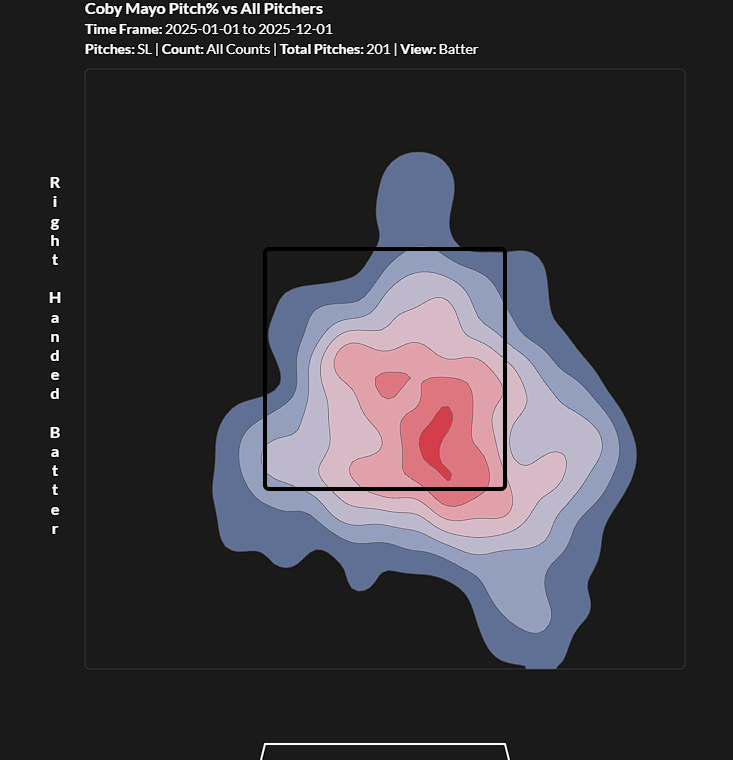

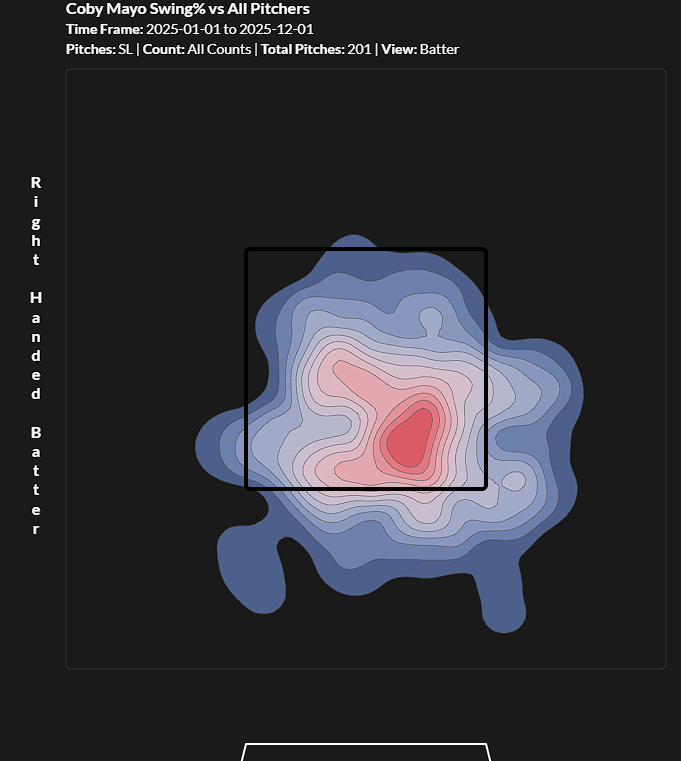

Honestly, that’s great news for our project. Want to fix Mayo? Stop him from rolling over pitches on the outer half. Given the big discrepancy in groundball rate, the most likely problem here is that too much of Mayo’s middle-away contact comes on pitches he can’t handle. It’s also bad news for our project, though, because Mayo’s greatest weakness is an inability to lay off sliders, and the right/right sliders he faces most often disproportionately end up on the outer half of the plate. In graphical form, here’s where pitchers throw him sliders:

And here are his swing decisions when facing those:

In plain English, pitchers frequently throw it to his weakest spot, and he swings a ton there even though he doesn’t do much when he connects.

Oh, a weakness to sliders? Very unoriginal, Ben. Every hitter is weak against sliders. That’s why pitchers throw sliders! But seriously, Mayo is particularly vulnerable to that particular breaking pitch, and the league knows it. There have been 331 hitters who have seen 750 or more pitches this year. Only two of them, Jorge Soler and Logan O’Hoppe, have seen sliders at a higher rate than Mayo’s 32.4% mark. He has the seventh-worst performance out of those same 331 hitters against sliders, and that’s on a per-pitch basis. Sliders are burying Mayo, in other words.

I’m confident that I’ve isolated the key issue holding Mayo back from replicating his minor league success. Now we just need to turn our knowledge into a plan. You might think that the answer would be “swing less.” Swinging less tends to improve a batter’s ability to select pitches; the choosier they are, the more often they choose a good pitch to hit. The problem is that Mayo already lives by the “swing less” philosophy. He’s in the 17th percentile for early-count zone swing rate, my favorite aggression proxy. He’s even more selective against in-zone breaking balls in those counts, in the fifth percentile for swing rate.

To recap, Mayo has an issue with sliders, and he has that issue despite being very choosy at the plate. That might sound like an unsolvable riddle, but there’s an Alexandrian solution: start swinging more. Yes, the big hole in Mayo’s game has been an inability to find pitches to drive. Yes, he’s putting up poor numbers even when he makes contact over the heart of the plate. Still, though: more swings, please.

It sounds wrong, but here’s why I think it would work. If you want to hit a fastball in the strike zone, you should either get ahead in the count like Juan Soto or attack early like Bryce Harper. The Soto plan is probably ambitious for Mayo; he’s chasing more often than league average despite swinging at strikes less often than league average. Now, it’s not like Mayo has the strike zone judgment and innate feel for hitting of one of the best hitters of the 21st century either, but he can still learn something from Harper’s approach.

Here are some facts. In the first two pitches of Mayo’s plate appearances this year, 33% of the pitches he’s seen have been fastballs in the strike zone. In neutral hitting counts – fewer than three balls, fewer than two strikes – that rate is 33% again. It falls to 21% with two strikes, though, and 19% when there are more strikes than balls in the count overall. Pitchers aren’t dummies – they’ve all read the scouting report, and they all throw nasty sliders these days. He sees roughly 40% sliders after he’s behind in the count.

Thanks to his weakness against breaking balls, Mayo has been pretty much doomed after falling behind in the count. In run value terms, only Michael A. Taylor has had worse results after falling behind, even relative to the league’s overall poor performance in pitchers’ counts. Few hitters have been worse than Mayo with two strikes. Combine a big swing with a weakness against breaking balls and you’re gonna be in for a rough time.

The Magical Christmas Land solution, where everything works perfectly, is for Mayo to correct that down-in-count weakness. I’m interested in real world solutions, though. Why not just swing more often at the early-count fastballs? That seems too easy, and there are of course plenty of downsides to that approach, but it still seems like a great option to me.

Hitters exercise caution early in the count to get ahead late. It’s a great theory, but it’s not working for Mayo. He gets ahead in the count about as often as Luis Robert Jr. or Jeff McNeil, which is to say not very often. He’s willing to take a pitch, which is half of the equation, but pitchers aren’t cooperating. On the first pitch of the at-bat, pitchers are treating him like a slap hitter; his 60.2% zone rate to lead off at-bats is in the 93rd percentile. As we’ve already covered, he’s ultra-selective in these counts. The result? A lot of called strikes and tough counts. As we’ve also already covered, Mayo is one of the worst hitters in baseball when down in the count. Not great, Bob.

Many great hitters take called strikes at a high clip. None of those guys have an enormous two-strike hole in their game, though. Those guys also aren’t facing enormous zone rates and attack mindsets on the mound. The trap Mayo has found himself in this year is understandable. His two-strike production is awful, so he’s trying his hardest to avoid chasing bad pitches and putting himself into tough counts. His only miscalculation has been that it takes two to tango.

My idealized version of Mayo swings early and often. He might end up in more disadvantageous counts, and that’s of course bad. But he’ll also do way more damage when he connects, because that’s how hitting works. Mayo’s own results this year tell the tale. When there are neither three balls nor two strikes in the count, his contact quality is great; he has a .624 slugging percentage and is producing at a .403 wOBACON clip, with peripheral batted ball data supporting the fact that he’s making good loud contact. His contact with two strikes is much worse: .429 slugging percentage, .222 wOBACON, barrel and hard-hit rates halved.

In other words, no more of this:

And definitely no more of this:

Is this a silver bullet solution? Definitely not. Honestly, if his 2025 results against sliders represent Mayo’s true talent level, there’s probably no fixing that. But let’s say he’s just garden variety bad against sliders on a going-forward basis, so that we can continue imagining a better future. That potential improvement against sliders won’t matter unless he figures out a way to take more swings at hittable fastballs. A power hitter with a strikeout problem is one thing. A power hitter with a strikeout problem who often waits to swing until there are two strikes is something else altogether.

Hitting is hard in the best of circumstances. Mayo’s decisions have made his own circumstances worse, though. Those two bad takes I showed up above were pivotal, and also representative. In each case, the pitcher got ahead in the count easily and started working the outside edge with tougher pitches. Mayo went down just as easily each time, on a called strikeout and a weak grounder. Two videos of bad takes don’t prove a point – but, well, Mayo’s season doesn’t exactly prove that his current approach is working, either. I can imagine a gloriously Mayo-filled future, and as I envision it, he’s a swing-first demolisher who figured sliders out just enough to turn fastballs into souvenirs at an enviable rate.

Content Source: blogs.fangraphs.com