David Hamilton doesn’t wait casually at first base. He lurks, waiting for the slightest opening to take off. Watch an at-bat where Hamilton is on the bases, and he’s often as much a point of discussion as the man at the plate. Take the game between the Red Sox and Guardians on September 1, for example. Hamilton pinch-ran for Carlos Narváez with Connor Wong at the plate. Wong fouled off a bunt for strike one with the entire defense focused on Hamilton at first base. Then Hamilton stole second on the next pitch even with the catcher, pitcher, and infielders all fixed on his every move.

Hamilton isn’t the most prolific basestealer in the majors. He isn’t the most successful. But he is the baserunner who tries to steal most frequently, after adjusting for opportunities, and so he’s a great poster boy for what I’d like to talk about today: stolen base opportunities and takeoff rate.

It doesn’t take much to make a stolen base possible, just a runner and an open base. You do need both of those, though. Draw a walk to load the bases, and you’re not attempting a steal without something very strange going on. Stolen base opportunities aren’t easy to find in a box score or a game recap. They’re the negative space of baseball – no one’s counting them, and it’s easier to see where they aren’t than where they are. So, uh, I counted them.

To do so, I first made a definition. I’m defining a stolen base opportunity as a plate appearance where, for at least one pitch, a runner on first base sees second base unoccupied or a runner on second base sees third unoccupied. In other words, if a plate appearance happens where the runner could have stolen without it having to involve multiple baserunners going at once, that’s a stolen base opportunity.

From there, I threw game logs for the 2025 season into my computer and told it to compile stolen base opportunities from every plate appearance of the year, for every baserunner who reached first at least once. Then I merged that with a database of actual stolen base attempts. This gave me both opportunities and attempt rates, what I’m calling takeoff rate for the remainder of this article.

Hamilton, for example, has racked up 34 opportunities to steal second and 23 to steal third, for 57 total opportunities. He’s attempted 24 steals. That means that 42% of the time that he can go, he does go. That’s almost unfathomably aggressive, the highest mark in baseball. It gets at what I think is the true mark of a basestealer: Everyone knows he’s going, and yet he goes anyway. He doesn’t have the best success rate in the league because he’s running in some tough spots for steals, and he doesn’t have the most stolen base attempts because he’s not an everyday player, but when it comes to production per opportunity, no one is pushing the envelope more than Hamilton.

In fact, almost no one is even close. Here are the 10 baserunners who attempt to steal most frequently when given the chance (minimum 25 opportunities to steal second):

Stolen Base Attempt Rate, 2025

I gave short shrift to Caballero by making Hamilton the poster boy for this statistic, but hey, someone has to be in first place. Caballero is nearly as likely to go for it as Hamilton, and between playing everyday and an 80-point edge in OBP, he has a lot more opportunities. The two of them stand alone at the top of the majors when it comes to turning stolen base opportunities into attempts.

The top of this list does a great job of highlighting the do-everything basestealers who are as fast as they are skilled. There are no slowpokes on this list of 10, no Juan Soto sneak attacks. If you’re attempting to steal this frequently, a quarter of your opportunities or more, that implies a combination of speed and desire. Many of these guys are part-time players, too. Limit the list to everyday regulars, and you’ll see the addition of many of the players considered the best baserunners in the game:

Stolen Base Attempt Rate, 2025, Regulars

| Player | Steal 2nd Opps | Steal 3rd Opps | SBA | Takeoff Rate | SB% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| José Caballero | 76 | 54 | 51 | 39.2% | 82.4% |

| Chandler Simpson | 111 | 58 | 50 | 29.6% | 78.0% |

| Luis Robert Jr. | 85 | 56 | 41 | 29.1% | 80.5% |

| Pete Crow-Armstrong | 81 | 70 | 38 | 25.2% | 81.6% |

| Oneil Cruz | 103 | 76 | 40 | 22.3% | 90.0% |

| Victor Scott II | 98 | 53 | 33 | 21.9% | 93.9% |

| José Ramírez | 123 | 74 | 43 | 21.8% | 83.7% |

| Jazz Chisholm Jr. | 99 | 41 | 30 | 21.4% | 86.7% |

| Elly De La Cruz | 129 | 68 | 38 | 19.3% | 84.2% |

| Jacob Young | 95 | 30 | 24 | 19.2% | 58.3% |

| Bobby Witt Jr. | 147 | 99 | 42 | 17.1% | 81.0% |

To me, this is a different category than the list Hamilton leads, and Caballero is the clear best here. If you have this many opportunities to steal, you’re assuredly playing every day, which means that many of your stolen base opportunities won’t be tailor-made for you to go. Part of the reason Hamilton’s takeoff rate is so high is that he frequently comes into the game as a pinch-runner in situations where a steal is beneficial. Bobby Witt Jr. ends up on first base in a 7-2 game in the ninth a lot more frequently because he plays a lot more frequently, and that lowers his takeoff rate even if it doesn’t lower his overall skill as a basestealer.

I showed this slice of the list largely to highlight Jacob Young, who is pretty much the only high-volume basestealer who hasn’t been very successful this year. Of the 56 everyday players have takeoff rates of 10% or higher this season, Young has the lowest stolen base success rate, at 58.3%. Only four other players (Tyler Freeman, Jordan Beck, Caleb Durbin, and Andy Pages) are even below 70%. Young is blazing fast and stole 33 bases a year ago; he might just be a victim of his own success, attempting too many steals because he was so good at safely doing so last year. He might also just be suffering an unlucky stretch. The point is that he stands out; most baserunners who attempt to steal on even 10% of their opportunities do so because they’re incredibly successful.

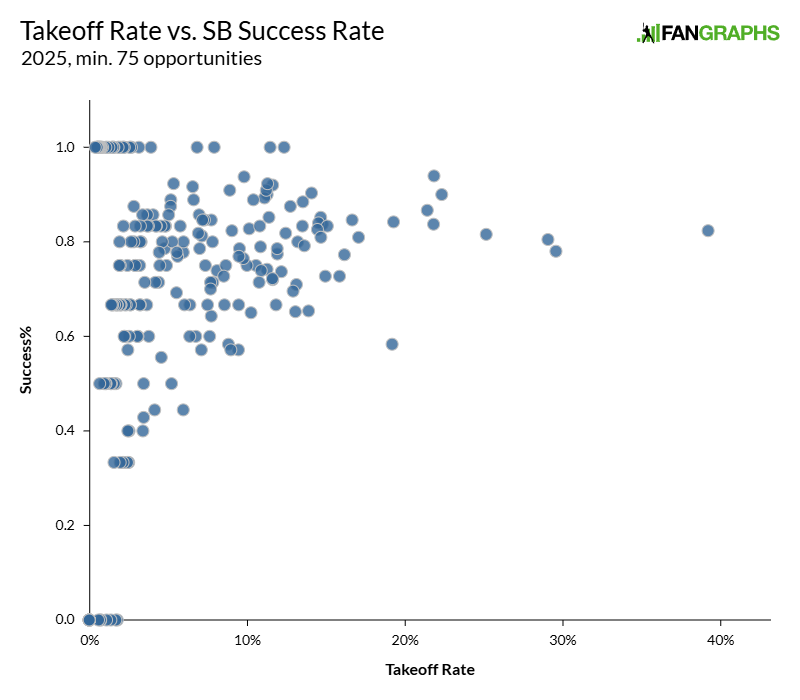

Graphically speaking, it looks like this:

You don’t need to draw a trendline or anything like that; a simple visual inspection will do. Low-frequency basestealers are mostly low-frequency basestealers because they aren’t good at stealing bases. That’s why the lowest success rates are all for players with low takeoff rates. By the time you get up above a 10% takeoff rate, though, there’s little correlation between propensity to steal and likelihood of stealing safely.

Should we slice the data up another way? Let’s slice the data up another way. How about the guys with the most stolen base opportunities, the Always On Base Club? Imagine if Rafael Devers ran like David Hamiltion:

Most Stolen Base Opportunities, 2025

That’s all the players with 250 or more stolen base opportunities in 2025. This list doesn’t sort by stolen base prowess like the others I’ve displayed so far; instead, this is basically a mix of OBP, availability, and batting order. Devers is hardly the only plodder on the list; 11 of the 24 have takeoff rates below 5%. The interesting list is the players who are always on base and also run frequently:

High-OBP High-Takeoff Hitters

| Player | Steal 2nd Opps | Steal 3rd Opps | SBA | Takeoff Rate | SB% | Sprint Speed (ft/sec) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trea Turner | 180 | 111 | 43 | 14.8% | 83.7% | 30.3 |

| Geraldo Perdomo | 183 | 103 | 29 | 10.1% | 82.8% | 27.2 |

| Brice Turang | 189 | 86 | 31 | 11.3% | 74.2% | 28.9 |

| Juan Soto | 177 | 89 | 30 | 11.3% | 90.0% | 25.9 |

| Fernando Tatis Jr. | 161 | 104 | 33 | 12.5% | 81.8% | 28.7 |

| Xavier Edwards | 173 | 87 | 31 | 11.9% | 77.4% | 28.3 |

| Kyle Tucker | 162 | 90 | 28 | 11.1% | 89.3% | 26.5 |

| Francisco Lindor | 158 | 93 | 32 | 12.7% | 87.5% | 27.3 |

That’s right: Soto is a track star now. The potential 40/40 man is an outlier in this list of eight prolific thieves. Look at how slow he is compared to them! Could there be more Soto types lower in the ranks, runners with the chops to steal bases at a high clip but who simply aren’t taking advantage of their talents? Maybe – though probably none quite as good as Soto is at it. Here are some very successful basestealers who are nevertheless not stealing all that frequently:

High Success Rate, Low Takeoff Rate

I’m not surprised to see a list of great baserunners who aren’t as young as they used to be. Springer and Semien have been great on the basepaths for a decade and still pick their spots quite well; I expect that they couldn’t increase their takeoff rate without seeing their success rate drop off as a result. Profar, Albies, and Acuña might be on the list because the Braves have asked them to run less; they’re all pretty good and pretty successful, but I don’t expect them to pick it up given that they haven’t yet this year. Acuña, specifically, could steal a lot more but chooses not to, probably because he is coming off his second ACL surgery within the last five seasons.

The most interesting names here, for me, are Cam Smith and Junior Caminero. Neither of them stood out on the basepaths in the minor leagues, but they’re doing an excellent job so far in the majors. Smith, in particular, will probably keep stealing more as he adjusts to the big leagues. He’s quite fast and a good baserunner even excluding steals; I think that he’s a candidate to take a big leap here, as he could afford to have his success rate decline meaningfully as long as he takes off more often. Caminero is more interesting in a Soto sort of way; he’s not particularly fleet of foot, but seven swipes and only one time caught stealing suggests that he could look into running more. I’m a lot more convinced by Smith, though. Shout out, too, to Kyle Schwarber, who has been doing his own Big Sneaky Man act for years now. Is he fast? No. Is he successful? Indubitably.

Like Michael Rosen’s research on trail runners, I think that this look at stolen base rate through the lens of opportunity is focused on a very small edge in the game. For the most part, better basestealers steal more often and more successfully. That said, I think there’s value in looking at the outliers, guys like Caminero and Hamilton and Soto. Knowing how frequently a runner turns chances into stolen bases might not tell us a lot about how much value they add – our baserunning statistics already have that covered – but they can provide valuable context for how the best in the game eke out extra value on the bases. Finally, here’s a sortable list of stolen base opportunities, takeoff rate, and success rate for everyone who has had at least one opportunity to steal in 2025.

Statistics current through Friday, September 5.

Content Source: blogs.fangraphs.com