On Wednesday, the Yankees went to Daikin Park for the middle game of an important three-game set against the Astros. The Yanks were 2 1/2 games behind the Blue Jays in the AL East with the two divisional foes scheduled for three games in the Bronx this weekend, so maybe this matchup with Houston wouldn’t have a direct impact on their place in the standings, but every win helps at this point in the season.

With the game tied 4-4 in the bottom of the eighth, manager Aaron Boone called on Devin Williams to hold the line. Williams, a two-time All-Star and the 2020 NL Rookie of the Year, came to New York this past offseason after posting an ERA under 2.00 in each of his last three seasons with Milwaukee. This season, his last before he hits free agency, has been… uneven, let’s say, and I’ll get to that.

Still, through all the ups and downs, Williams has remained one of Boone’s high-leverage guys. He’s a big-time reliever, and a tie game on the road against a major postseason rival is a big-time situation. So on Williams came.

He quickly got up 0-2 on Carlos Correa with a pair of his signature Airbender changeups. Correa declined to chase a third, so Williams came back with a fastball.

Not a great pitch — probably caught too much of the outside corner — and while Williams put it in a place that was hard to pull for a home run, Correa has been tucking his hands in and flicking outside fastballs down the right field line since the latter days of the Obama administration. It happens. We go again.

Williams walked the next batter, Jesús Sánchez, on five pitches. Statcast shows that the first two fastballs caught the upper corners of the zone, but were called balls by home plate umpire Brian Walsh. Williams would have reason to be aggrieved, but the first pitch, especially, had such wicked late movement I see why Walsh missed the call.

Also, Austin Wells has done better framing jobs in his career. Tough break for Williams getting down 2-1 in the count, but once there, he followed with two not-especially competitive changeups.

A leadoff double is an issue. A leadoff double followed by a five-pitch walk is a snowballing crisis. Williams did well to retire Yainer Diaz on a nine-pitch strikeout. In the interest of balance, I’ll show you the positively nasty right-on-right changeup that did Diaz in.

But now Williams, as pure a one-inning reliever as you’ll find, was already up to 18 pitches with two more outs to get. And when he walked Christian Walker on six pitches to load the bases, his arm only got more tired as his predicament got worse.

Williams climbed the ladder on Ramón Urías and got him to chase a 2-2 fastball, leaving him one batter from escape. Retire Taylor Trammell and everything would be fine.

Unfortunately, Trammell drove in the go-ahead run without taking the bat off his shoulder. Williams got squeezed again on an up-and-in fastball — almost a carbon copy of the borderline call he’d lost against Sánchez. And when the decisive 3-1 pitch came, Williams threw a pretty good changeup: nasty movement, just below Trammell’s knees.

But let’s get into Trammell’s shoes here for a moment. You’re up 3-1 in the count, with the bases loaded, against a pitcher who’s already thrown 33 pitches and walked two batters in the inning. I wouldn’t go out of my way to defend the edges of the zone in that situation. Neither, it seems, would Trammell.

Never interrupt your enemy when he’s making a mistake.

That was enough for Boone, who replaced Williams with Camilo Doval, then watched as Doval immediately made the situation worse. A single, a bases-loaded balk, and a wild pitch brought home all three inherited runners and gave the Astros just enough margin to survive a Yankee comeback in the top of the ninth.

Williams has had a hard time of it over the past week; in his last outing before the meltdown in Houston, he blew a save against the White Sox. That means that over the past week, he has allowed five earned runs and eight baserunners over the course of 11 batters faced. His ERA has leapt up nearly seven-tenths of a run, to 5.60.

That’s a nightmare, especially in a position — “Yankee closer” — where the standard is literally perfection. Nowhere else in baseball have the fans been so completely spoiled by a historical outlier. Nowhere is the curve so entirely broken.

It’d be one thing if Williams were just completely cooked, if the Brewers had gotten out of the Devin Williams business at exactly the right moment. But I’m not convinced that’s true.

Wednesday’s outing was a microcosm, you see. I’m not going to say that Williams, who allowed three walks and an extra-base hit in a high-leverage situation, deserved better than what he got. The last time I was on Effectively Wild, Meg asked me what the worst way to lose a baseball game is. My answer was basically what Williams put the Yankees through: when a high-leverage reliever just cannot stop walking people. It’s the kind of excruciating slow-motion death that makes a person believe in Hell.

For that reason, I don’t expect Yankee fans to give a little bit of a crap whether Williams has been truly bad or just unlucky this year. High-leverage relief is a results-based business. Anyone who says the words “BABIP monster” after a closer blows a lead is probably going to get (deservedly) a drink thrown in their face.

But the difference between disaster and a routine clean inning was three borderline strike calls and maybe a couple inches of movement on the 1-2 fastball to Correa. Moreover, the inning didn’t turn into a nightmare until Doval came in and poured paint thinner on the embers. A poor performance was made to look like a total fiasco through factors that were at best only kind of within Williams’ control.

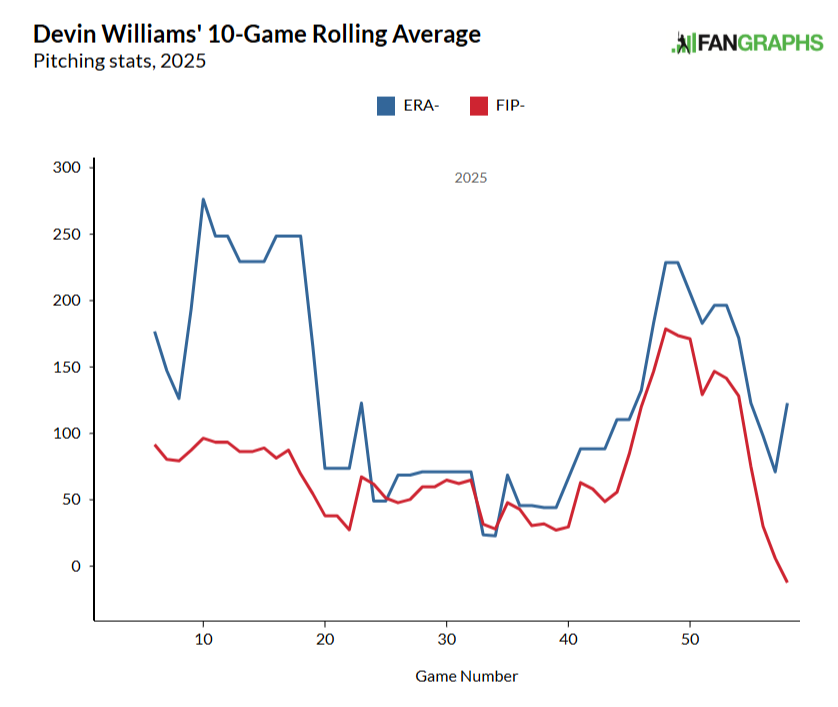

What am I talking about? Take a look at this.

Williams got off to a rough start this season. In his first 14 games, he allowed three or more earned runs as many times as he pitched a clean inning (four times each). His ERA was over 10.00 as late as the first week of May.

But over his next 42 appearances, Williams had an ERA of 3.40, with 61 strikeouts and only nine unintentional walks in 39 2/3 innings. In those 42 appearances, the Yankees went 30-12, a winning percentage of .714. Over parts of six seasons, the Brewers went 191-64 when Williams pitched, for a winning percentage of .749. If he was worse during that stretch than he was at his peak, it wasn’t by a huge amount.

In fact, that blown save against the White Sox busted up a run of eight appearances in which Williams had struck out 18 of the 25 batters he faced, while allowing just three baserunners and a single unearned run.

Even if you factor in the rough patches at either end of the season, Williams’ underlying numbers remain respectable, if not downright good. He’s still striking out 34.7% of opponents, which is down from his peak in the low 40s, but still seventh among qualified relievers. It’s fair to ding Williams for his double-digit walk rate (especially after what went down on Wednesday), but his K-BB ratio is still 14th among qualified relievers.

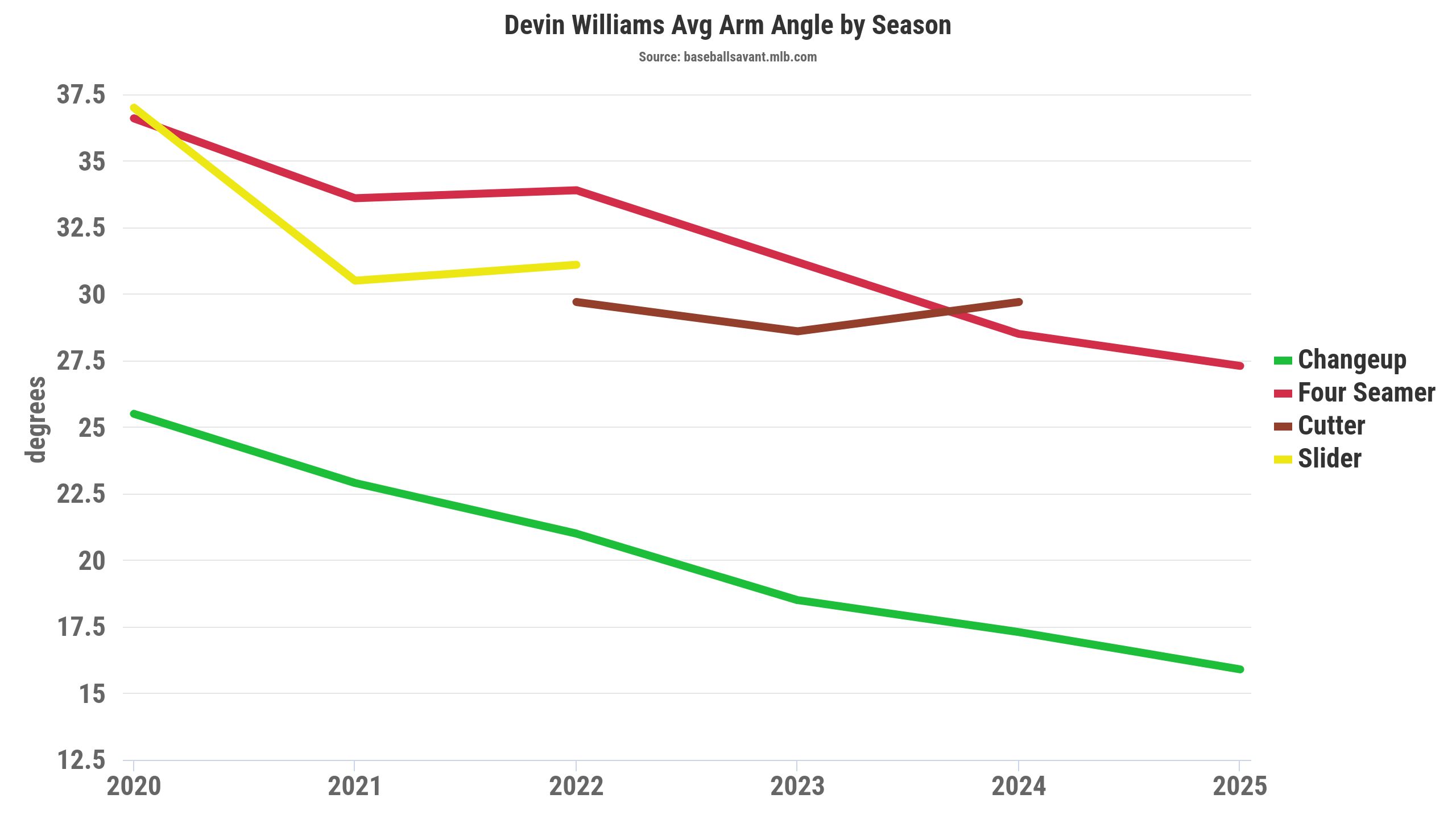

Mechanically and stuff-wise, the only yellow flag I see from Williams is that his arm angle is sagging a little. It’s dropped about two degrees a year since his rookie season, and it’s down to 21 degrees in 2025. But that’s a gradual process that’s unfolded over his entire career, not a sudden change in release point that came out of nowhere this spring.

Is the lower release point messing with Williams’ stuff? I guess it’s possible, but he’s still in the 98th percentile for chase rate, whiff rate, and strikeout rate. His fastball and changeup are still coming in at the same velocity they always have, with the same movement.

What’s really cooking my noodle, so to speak, is this: Williams has a 5.60 ERA this year, but only a 2.95 FIP and a 3.17 xERA. As many of you probably already know, that is a massive, massive incongruity on both counts.

It’s the fourth-biggest discrepancy between xERA and ERA this year. The only players who are getting screwed more by luck and/or clustering this year are Cole Ragans (injured), Bradley Blalock (pitches for the Rockies), and Jordan Romano (don’t ask, I don’t want to talk about it). The difference between Williams’ ERA and FIP is the third largest among pitchers who have thrown at least 40 innings, trailing only Romano and Ragans.

So is it luck, or is it clustering?

Well, there are a couple fluke indicators. Williams is running a .304 BABIP this year, which is higher than his .250 mark last year and his career average of .260 heading into this season. Opponents are also making contact on 56.4% of swings outside the strike zone, which is not unusual globally but it’s downright bizarre for Williams, who’s one of the chasiest and whiffiest pitchers in all the land. His O-Contact% last year was 44.9%, nearly identical to his career average of 44.8%.

When hitters make contact outside the strike zone against Williams this year, they’re hitting .325 and outproducing their xwOBA by 50 points. The league-wide batting average on contact outside the zone this year (including foul balls) is .282. From 2022 to 2024, Williams’ opponents hit just .169 on contact outside the zone.

But the outlier fluke indicator that got me worried was Williams’ left-on-base percentage: 50.0%, the second worst of any qualified reliever in baseball. Only Romano, with his ERA of 8.23, has been worse in this respect.

That’s so far outside the norm it has to be a bad sign. If you roll snake eyes twice in a row, that’s bad luck. Even two, three, maybe four times in a row. If you roll snake eyes 18 times in 20 throws, there’s something wrong with the dice.

If Devin Williams Were Any Worse With Men on Base, They’d Have To Call in the Military Police

| Runners? | wOBA | xwOBA | Whiff% | HardHit% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bases Empty | .245 | .243 | 38.8 | 30.8 |

| Runners On | .334 | .335 | 36.3 | 41.8 |

| RISP | .311 | .317 | 36.3 | 35.1 |

Source: Baseball Savant

What’s going on with Williams with men on base?

Well, the place I wanted to start was the more than 11-degree difference in arm angle depending on whether Williams is throwing a fastball or a changeup. That’s visible to the hitter for sure. Kirby Yates, to give another example of a fastball/offspeed reliever who’s struggled with men on this year, has less than a one-degree difference.

But that separation not only persists regardless of base-out state, it’s been there throughout Williams’ career.

Let’s see if anything goes haywire with Williams’ control, based on who’s on base and where.

If Devin Williams Were Any Worse With Men on Base,

They’d Have To Call in the Military Police, Part 2

| Runners? | FF Zone% | CH Zone% | FF In-Zone wOBA | CH In-Zone wOBA | FF O-wOBA | CH O-wOBA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bases Empty | 50.4 | 43.6 | .269 | .292 | .328 | .098 |

| Runners On | 51.7 | 39.1 | .198 | .447 | .462 | .268 |

| RISP | 51.1 | 39.2 | .168 | .286 | .502 | .315 |

Source: Baseball Savant

In the process of making this chart, I accidentally sliced the pie so thin I was able to find out that Williams is getting killed on changeups in the zone with a runner on first, and only a runner on first. That’s a sample of just 24 pitches all year, and included in those 24 pitches are just six balls in play.

Included in those six balls in play are four of the 17 extra-base hits Williams has allowed this year, including two of his five home runs. Opponents have a wOBA of .904 when Williams throws a changeup in the zone with a runner on first, which is interesting, but perhaps not predictive.

My next theory was that Williams’ opponents were profiting by doing what Trammell did: Forcing him to throw strikes with men on base. With the bases empty, what the heck, go do the best you can. But when a walk can load the bases or force in a run, why give Williams what he wants?

Opponent Chase Rate by Year and Base-Out State vs. Devin Williams

| Year | Total Chase% | Bases Empty Chase% | Runners on Chase% | RISP Chase% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 33.6 | 32.9 | 34.9 | 30.8 |

| 2021 | 31.9 | 29.6 | 35.0 | 33.6 |

| 2022 | 32.3 | 32.4 | 32.2 | 29.8 |

| 2023 | 32.6 | 32.9 | 32.2 | 31.0 |

| 2024 | 29.4 | 35.4 | 20.9 | 23.3 |

| 2025 | 34.3 | 32.5 | 36.2 | 35.3 |

Source: Baseball Savant

Not so. If anything, opponents have been more aggressive this year against Williams, not less, with men on base.

But those pesky chase pitches are what’s killing him. From 2020 to 2024, Williams allowed six hits and two sacrifice flies, total, on pitches outside the strike zone with runners on base. In 2020 and 2024, hitters didn’t get a single productive outcome by chasing with runners on base.

This year, Williams has thrown 254 pitches outside the zone with men on base. From those pitches, he’s drawn 92 swings, generating 22 balls in play. That alone is unusual; it’s the highest figure since his 2019 call-up, both in raw numbers and as a percentage of total swings.

The real problem: Those 22 balls in play included 10 hits, or four more than Williams allowed in those circumstances across the rest of the 2020s put together. From 2020 to 2024, his opponents hit .143 with an xBA of .206 on balls in play from pitches outside the strike zone with runners on. This year, they’re hitting .455 with an xBA of .303.

Nine of those 10 hits were singles. Only one had a triple-digit exit velocity, and only four had an exit velo over 80. But those 10 hits drove in 10 runs, or 27% of the total output against Williams this year.

I think it’s fair to conclude that Williams is somewhat less than what he was at his peak. But he’s still doing what he’s always done, which is getting hitters to swing at pitches outside the strike zone in massive volume. I just didn’t know that it was possible to do that and get shelled anyway.

Content Source: blogs.fangraphs.com