Last week, I turned on the tail end of a Blue Jays-Phillies clash. I was hoping to get some notes for an article on Alec Bohm that didn’t really come together. The game was a complete laugher, with Philadelphia leading by five runs in the ninth. All I wanted was to see Bohm put a ball in play, but instead this happened:

Braydon Fisher came out firing in that low-leverage chance. He came out firing curveballs, to be specific – 12 of his 18 offerings in the inning. The Phillies swung at them like they were learning how physics works on the fly. But so what? Anyone can look that good for one game. Major league pitchers have good stuff, more at 11.

Then I started looking at Fisher’s prior games, and I started getting more intrigued. Wait, this guy almost never throws his upper-90s fastball? Wait, he has two different plus breaking balls? Wait, his walk rate was what in the minors last year (14.2%, and above 15% in Triple-A)? I started watching more at-bats and started getting interested. The slider? It’s nasty:

The key characteristic here is velocity. At 88 miles an hour, sliders don’t give opposing hitters much time to adjust. The tight gyro shape of the pitch means it works against lefties and righties alike. His over-the-top release gives the pitch a ton of downward plane, too: Though he doesn’t induce much break on the pitch, it seems to vanish downward when he locates it around the knees.

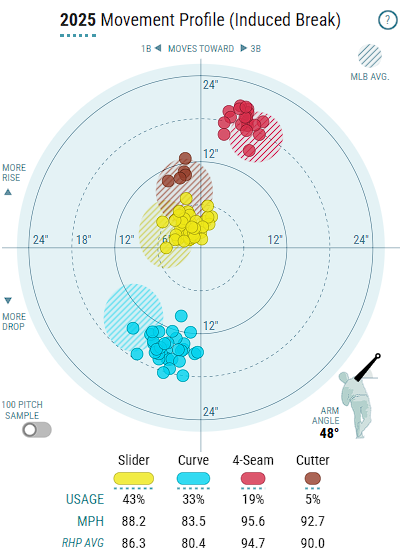

That’s Fisher’s primary offering. If you called it a cutter, that might make more sense; it’s a workhorse of a pitch, a grounder-inducing choice in the zone or a swing-and-miss weapon if he can run it just off the plate. It pairs quite well with his other offerings, sitting roughly between them on a chart of induced break (via Baseball Savant):

I love those little shaded areas that denote league-average pitch shape. Fisher is more up-and-down across the board; his slider and curveball break less to the glove side than most breaking balls, while his fastball is nearly pure vertical. His fallaway motion allows that verticality – watch again, and you’ll see that his body tilts left at the last second, so the same angle of separation between shoulder and arm can create a higher release point.

That flash of deception and vertical release help the shape and break of Fisher’s pitches. They do come with drawbacks, however. In the minors, Fisher struggled to throw strikes. That hardly seems surprising for a guy who rarely throws fastballs, throws hard, and uses a slightly unconventional delivery. That wildness held him back even as he posted excellent strikeout numbers in the minor leagues. It was also a key factor in the Jays’ getting him in the first place – he was traded for Cavan Biggio last summer when the Dodgers needed utility infield help.

The Jays didn’t institute any obvious fixes. Fisher finished 2024 in Triple-A Buffalo walking seven batters per nine innings, a 15.2% rate. But if you’ll take a quick gander at his 2025 player page, he’s made a change. He walked only 8.5% in a dominant minor league performance to start the season, and he’s become downright surgical since getting called up, with a 3.8% mark, a level that only pitchers with great command can sustain for long periods of time.

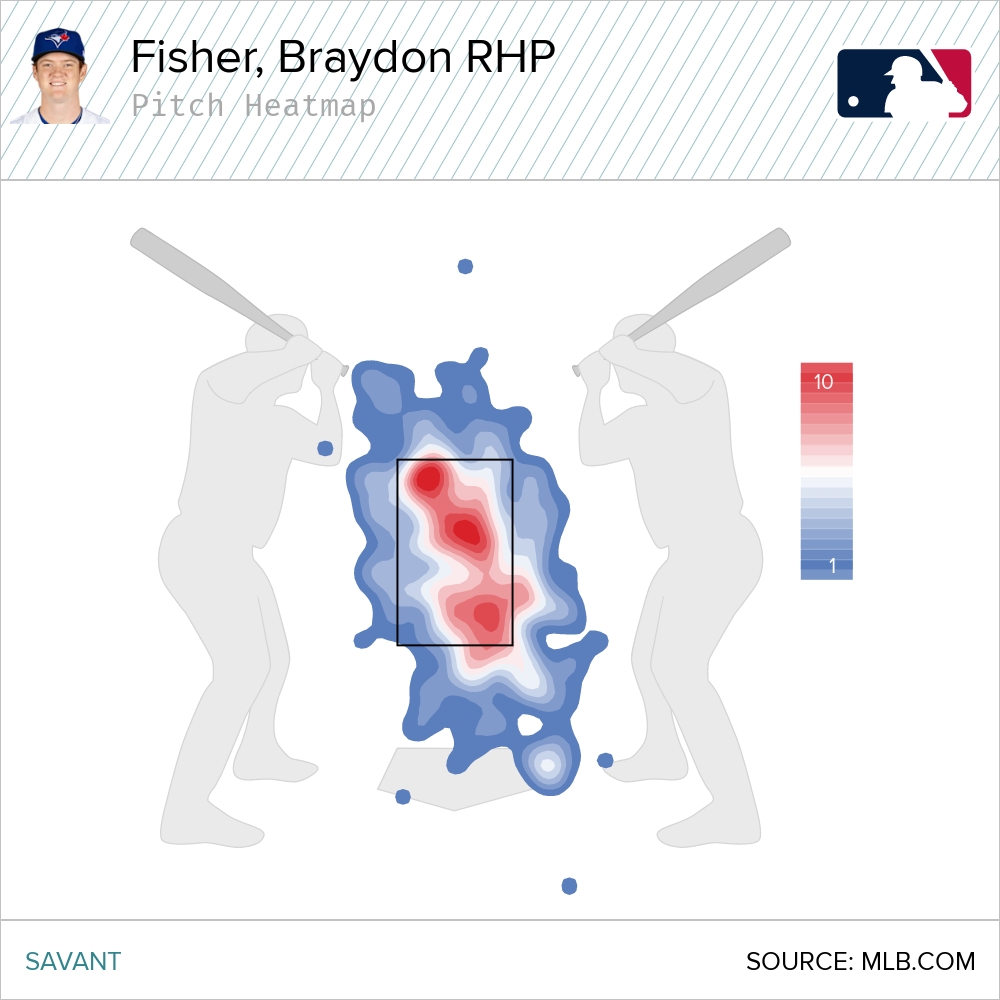

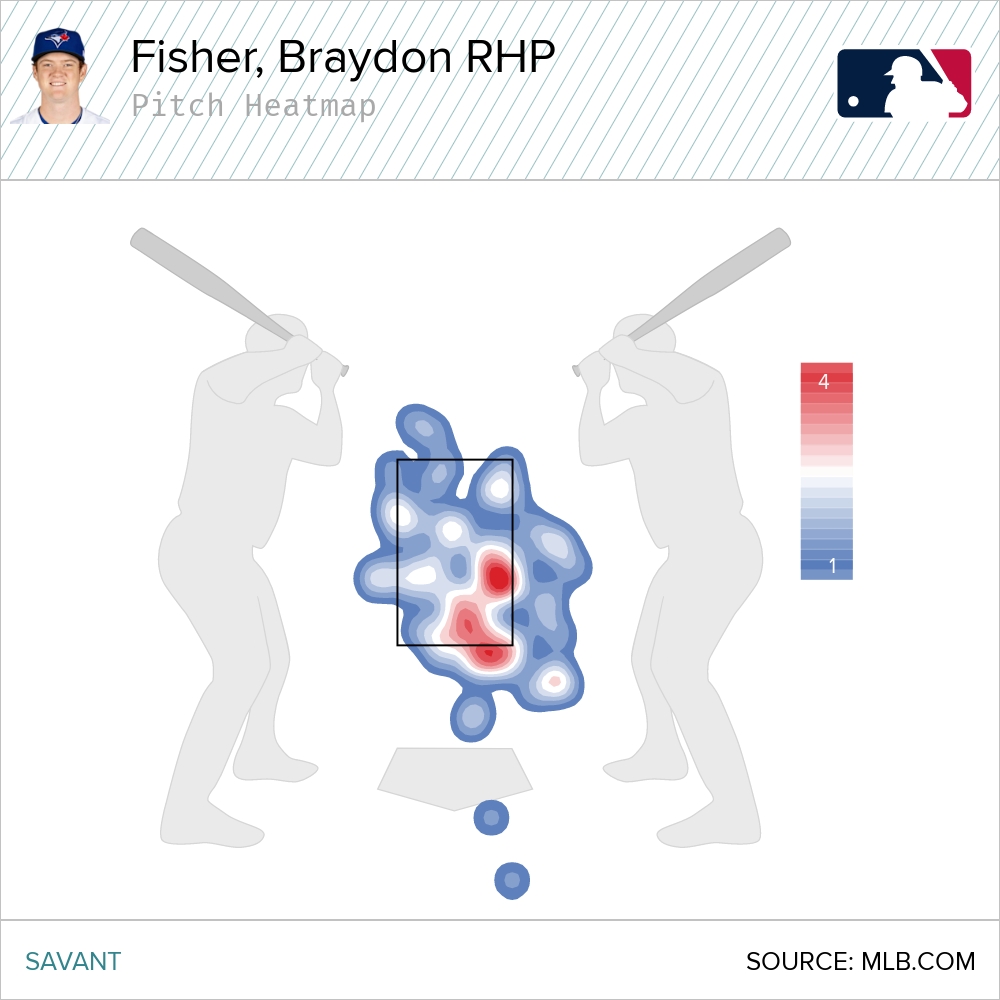

Just so we’re clear, I don’t think that he’ll keep this up. But I do think he’s made a big adjustment. Last year, Fisher ran his slider all around the zone. Here’s a heat map of every slider he threw in 2024, with the minor league affiliates of both the Dodgers and Blue Jays, in stadiums with pitch tracking:

Sure, that’s great utility, but a pitcher with inconsistent command moving a pitch to every corner like that creates plenty of opportunity for misses. He’s given up on a lot of the moving around he used to attempt, though. Now, he aims it low and to his glove side, and his misses are distributed around there in the shape of his release, up and in to a righty or down and away:

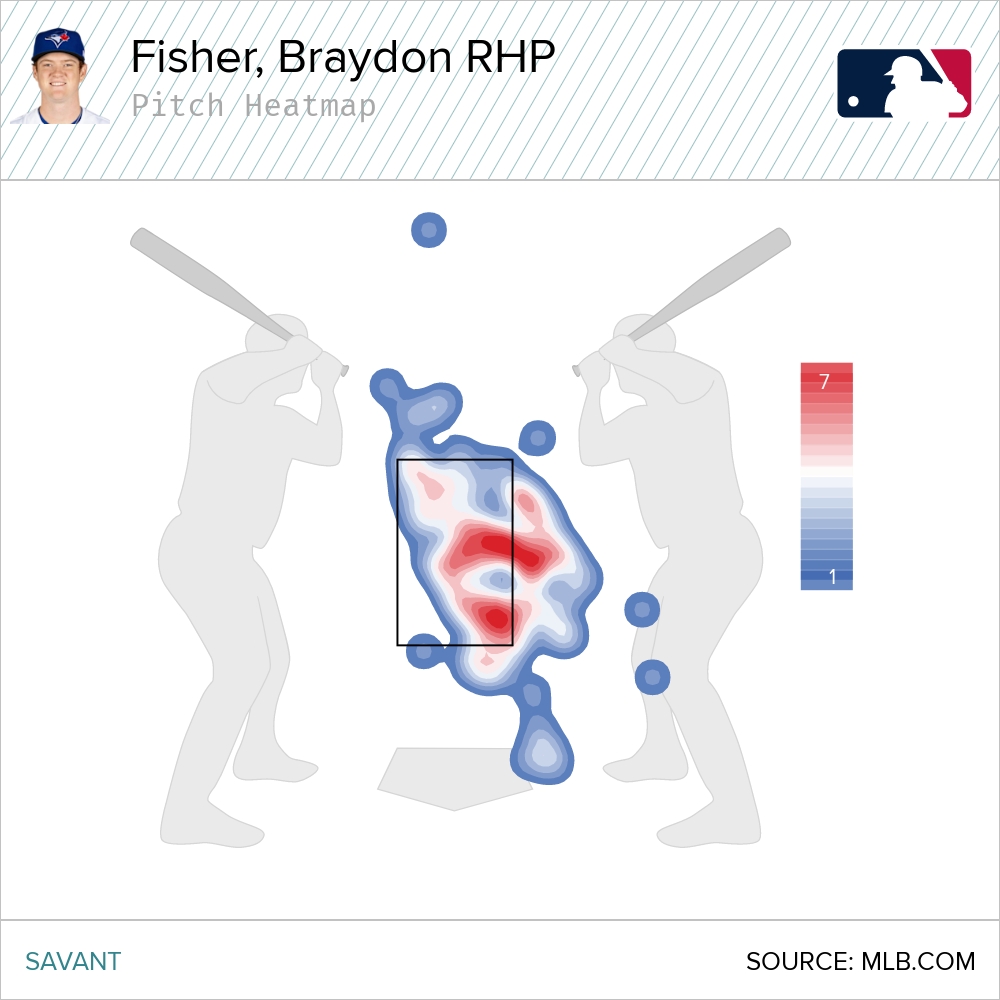

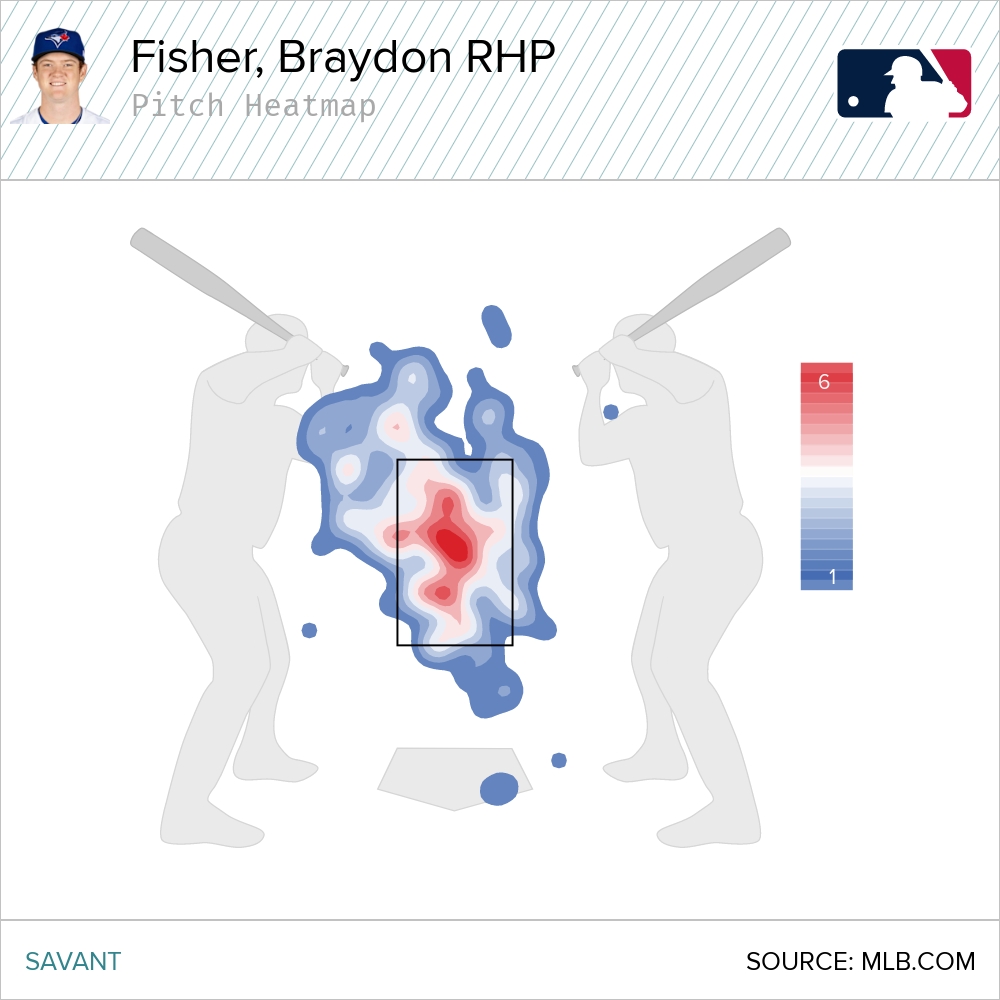

Similarly, Fisher threw a lot of high curveballs last year, and to look at his locations, you’d think he was trying to change the eye level of batters like peak Kyle Hendricks:

But that’s a very strange way to use a curveball, particularly a vertical one. This year, he’s just throwing it like a curveball:

He’s also landing it in the zone far more often, as you can probably tell from those charts. I’m not enough of a pitching mechanics expert to explain exactly how this works, but I can tell you one thing: Jays catchers have simplified their targets. They call for Fisher’s curveball with one of two glove positions: near the heart of the plate (normal), or with a tap on the ground (bounce it). And like Fisher’s slider, the curveball plays better down in the zone; his over-the-top delivery creates a nice, diving pitch shape down low, but is prone to “hopping” out of his hand up high.

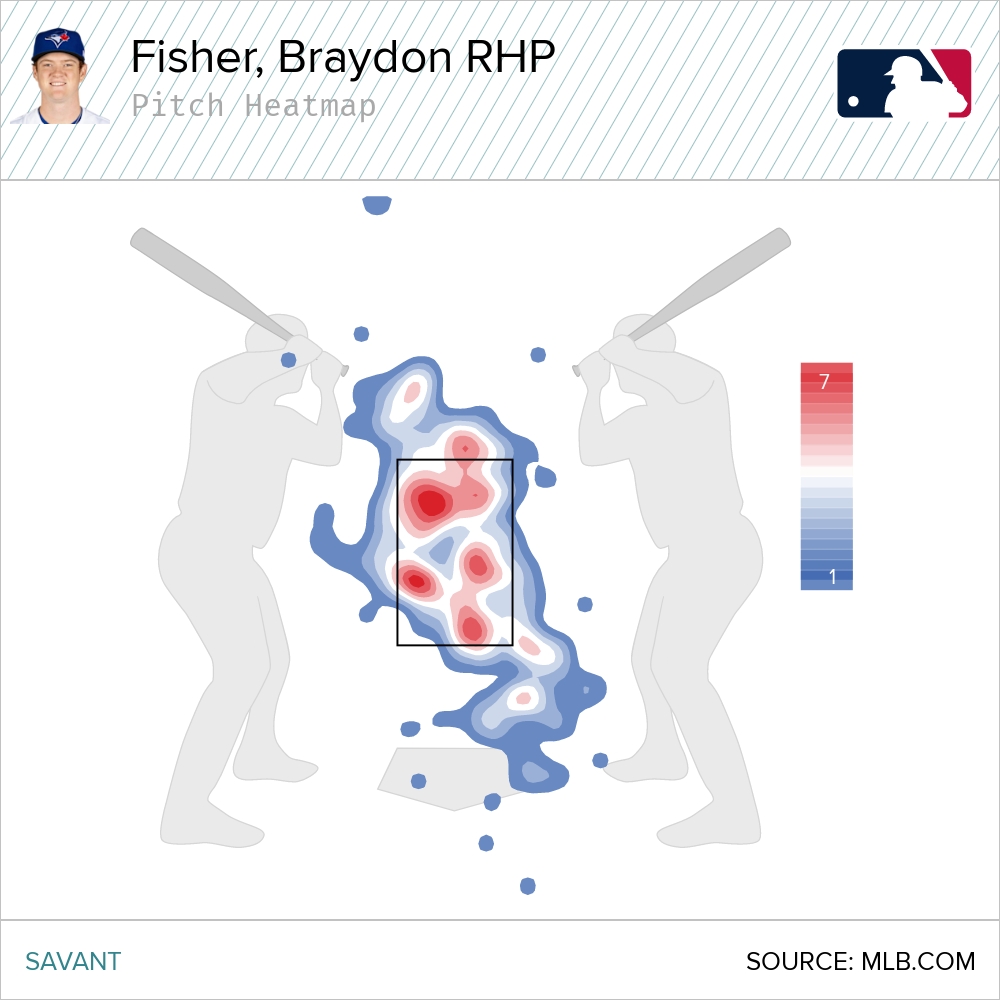

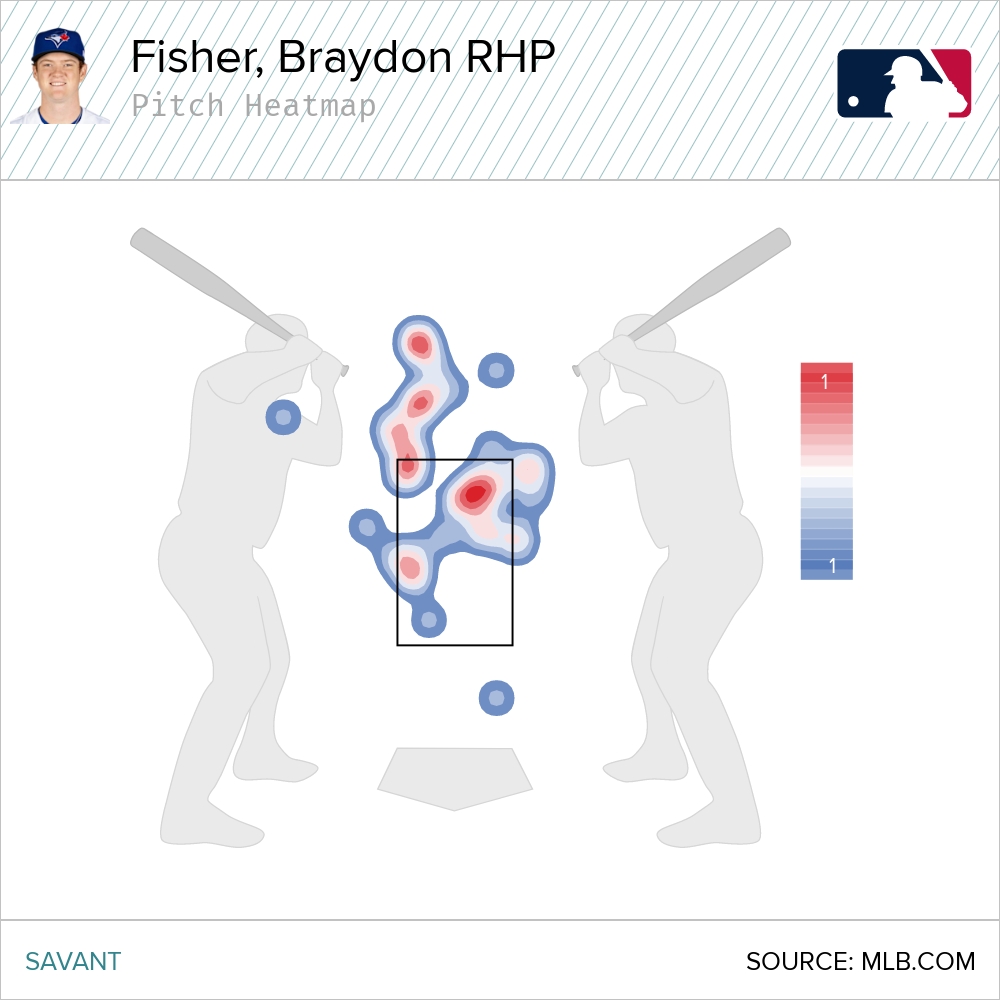

We might as well finish this heat map section off by looking at his fastball. This one is actually pretty interesting. Here’s the Triple-A location:

Sure, just cook it right down the middle. In the bigs this year, he’s doing something completely different:

I can explain this one. In the minors, Fisher still used his fastball about a third of the time; it was a co-primary pitch with his slider. He threw it a ton when he fell behind in the count, but generally speaking, he treated it like a regular fastball. It was his get-out-of-jail-free card, a solid option when he wasn’t quite sure what to throw. Now that he’s using it rarely – less than 20% of the time – he’s mostly hunting for swinging strikes above the zone with it.

I have to admit to bafflement here. The heat maps for 2025 are exquisite. Fisher has his slider and curveball on a string, and he keeps his fastball out of harm’s way. Everything tunnels off of each other: high fastballs, low sliders, lower curveballs. That’s how the best pitchers with Fisher’s arsenal – vertical, high release point, steep downward plane on the breaking balls – locate their options. Stack the three on top of each other, and you’re presenting the hitter with a tough decision every time you throw. Try to run all three all around the zone, like he was in Triple-A last year, and you’re liable to confuse yourself more than them.

Everyone would do this if they could, so I’m not entirely sure why Fisher hadn’t before this year. Regardless of how it happened, though, the fact of the matter is that right now, Fisher has plus command. He doesn’t have a deGrom-like feel for the zone; he’s not nibbling edges on demand with unerring precision. It’s a simpler style of knowing where the ball is going: Aim for a few trusty targets and let the natural movement do the work. But it’s still command, much more than he’s ever displayed before.

That command has unlocked something impressive. Fisher is striking out 34.8% of opponents in the majors this year. His two breaking balls are doing most of the work – those high fastballs just haven’t been consistently close enough to entice chases. But man, what work they’re doing. Opponents are chasing a ludicrous 50% of his sliders outside the strike zone. They’re chasing roughly 40% of curveballs, too, and plenty of those curveballs are bouncing before reaching home plate; he induces some ugly swings with that pitch.

Though our stuff models can’t quite decide what to make of Fisher – PitchingBot thinks both his breaking balls are below average and likes his fastball, while Stuff+ loves the bendy pitches and hates the fastball – I feel confident he has the requisite stuff to get big leaguers out. His minor league numbers bear that out. He’s repeating his delivery and attacking a particular zone. Combine those two, and you get a high-leverage, high-effectiveness reliever.

The Jays haven’t used him that way yet, but they’re trending in the right direction. I only saw him in the first place because he was mopping up the last inning of a blowout loss. But how can they not start bumping him up the hierarchy when he’s pitching like this? Over the last month, he’s running a 0.56 FIP and a 0.00 ERA. He’s getting into games in more important spots; sure, he still mops up some, but he also pitched in the eighth with a one-run lead and in the seventh with a two-run lead, traditional spots for a solid setup man.

If things go wrong for Fisher, I have a pretty good idea how. He’ll lose the feel for the zone, start getting behind 2-0 on two straight sliders, and have no clue how to get back into the at-bat. That delivery, that release point, that ugly minor league walk rate – there’s still wildness here, even if the results don’t show it yet.

Until then, though, I have a feeling Fisher will continue to excel. He’s a riddle to opposing hitters, a strange jingle whistled just out of tune that they can’t wrap their heads around. The slider-first approach, the curveball off of it – they’re weird. That weirdness is a huge asset for him, and now that he’s no longer walking nearly a batter an inning, that huge asset is paying dividends.

Content Source: blogs.fangraphs.com